The sales office for Forest City, one of Malaysia’s largest residential property developments, looks less like an office than an airport hangar or a museum atrium: a futuristic dome flooded with noise and light. At the entrances white-gloved guards offer a crisp salute. Nearby a band breezes through a set of pop standards. Prospective buyers–many of them from mainland China–lounge on couches sipping complimentary soft drinks while diddling on their cellphones.

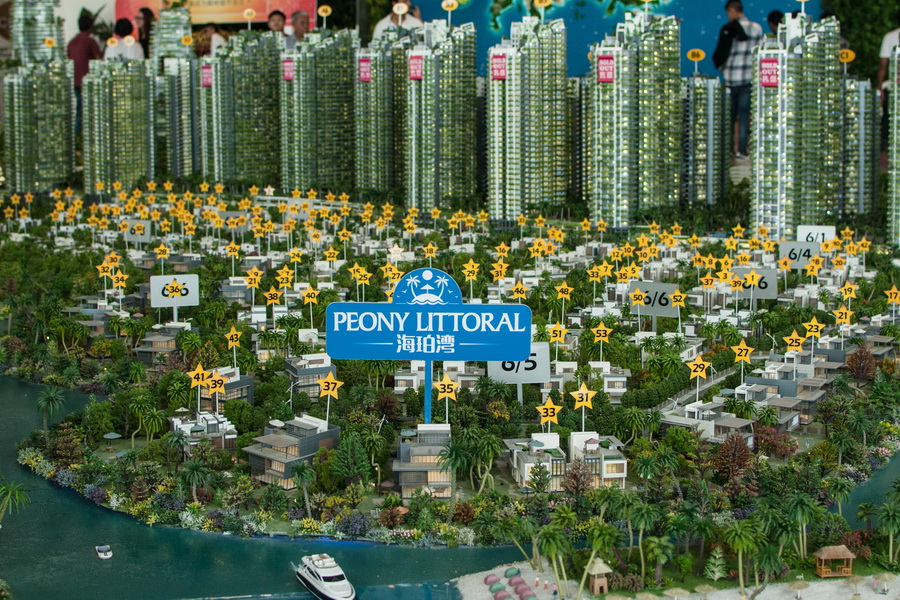

Sprawling in the middle of the hall is the main attraction: a giant scale model depicting the initial phase of the $100 billion project. Large groups of Chinese and Malaysian visitors snap photos of this vast field of roads, lakes, beaches, hotels, shopping malls and illuminated towers, some with miniature “SOLD OUT” labels attached.

The eye-catching model represents just one small part of the Forest City development, which is currently sprouting from the coast of Johor State at the southernmost point of peninsular Malaysia. “The whole scale model of this is Island One. We have four islands in total,” says Yu Ting, an English-speaking sales representative from Guangdong, the home province of the project’s Chinese developer, Country Garden Holdings. When completed in 2035, Forest City’s four islands will house an estimated 700,000 people in the Johor Strait, across from Singapore.

Describing the project as a “future city” and “a magnet for global elites,” Country Garden, which has partnered with a firm controlled by the Sultan of Johor to form the Malaysia-domiciled Country Garden Pacificview, is directing its main sales pitch at overseas buyers, particularly those from mainland China. Marketing materials focus on the project’s proximity to Singapore and the fact that its units cost around a quarter of what they do on the other side of the Johor Strait. Yu Ting tells me that in the year after sales began in March 2016, Country Garden sold some 16,000 units.

However, Forest City’s selling points–its massive scale and its targeting of affluent foreigners–has made it a lightning rod for political controversies about the growing extent of Chinese influence in Malaysia. In particular, critics have charged that Forest City will eventually become an enclave for rich mainland Chinese, cut off from the rest of the country.

Carrying the furthest is the singular voice of Dr. Mahathir Mohamad, Malaysia’s nonagenarian former prime minister, who ruled the country in energetic and authoritarian style from 1981 to 2003. In a stream of public comments and posts on his popular blog, he has repeatedly assailed Country Garden Pacificview and Johor’s powerful Sultan Ibrahim Ismail, accusing them of selling off the country’s “most valuable land” to foreigners.

In an interview with this reporter, Mahathir says he sees a historical warning in the Chinese-majority city-state of Singapore, which was expelled from newly independent Malaysia in 1965. “A country is created by the population,” he says, “and if the population is overwhelmingly of one particular race or another, then we will see that the country is no longer a part of the original owners of the land.”

To attract foreign buyers, Forest City will eventually feature its own customs and immigration checkpoint, facilitating quick travel to Singapore. It will also offer buyers various tax breaks and a path to residency under the government’s Malaysia My Second Home program, which is less stringent than gaining residency in Singapore. The company offers to front the nearly $6,000 application fee and guarantees a 99% success rate for applicants.

In an emailed message, Yu Runze, the firm’s president and chief strategy officer, says that the project was initially targeted at the Chinese market. He adds that it has since broadened out to other markets. “The Forest City township was planned and designed for the international market,” he says. “In fact, the buyers for the first phase of our residential units come from 23 countries.” According to Forest City sales staff, around 60% of sales have been to Chinese buyers.

The controversy over Forest City hints at wider political questions about China’s quickly widening economic footprint in Malaysia. Under the leadership of Prime Minister Najib Razak, who took office in 2009, the relationship between Kuala Lumpur and Beijing has grown close–some say too close.

Once a bit player in Malaysia, China has been the country’s largest trading partner for eight consecutive years, with bilateral trade volume topping $57 billion in 2016. It is now the country’s main construction contractor, the largest source of foreign investment in manufacturing and, despite a downturn following the disappearance of the MH370 flight in 2014, the third-largest source of foreign tourists to Malaysia. In his farewell speech last month, Huang Huikang, China’s outgoing ambassador, said that the Sino-Malaysian relationship “should move up over the next 40 years to reach mutual dependency, like lips and teeth.”

This strategically-located country of 32 million has also emerged as a key stop on Beijing’s 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, the maritime leg of its much-vaunted One Belt, One Road (OBOR) infrastructure scheme. The OBOR initiative, unveiled by Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2013, envisages linking China with Africa and Eurasia through a complex network of ports, roads, railways and industrial parks.

Under the umbrella of OBOR, Najib’s government has signed agreements for a slew of Chinese infrastructure megaprojects. At the top of the list is the $13.1 billion East Coast Rail Link (ECRL), which will run from Port Klang, Malaysia’s main port near the capital Kuala Lumpur, to Tumpat on the border with Thailand, bisecting the peninsula’s hilly interior. In October 2016 the Malaysian government inked a deal with three Chinese state-owned companies to build and manage a deep-sea port and Maritime Industrial Park on three more reclaimed islands off the city of Melaka on the west coast, part of the $10.4 billion Melaka Gateway mega-development. In turn, this will be complemented by a Chinese-backed industrial park and port refurbishment in Kuantan, in the east coast state of Pahang.

Malaysia’s OBOR bonanza also includes the new Malaysian campus of Xiamen University on the outskirts of Kuala Lumpur, and Bandar Malaysia, a real estate project that will host terminals for a planned high-speed rail connecting Kuala Lumpur to Singapore. (Chinese companies may be in the catbird seat for that deal too.) While Forest City sits somewhat apart from this string of state-led OBOR projects, it is clearly buying into the “New Silk Road” hype. Its sales office tellingly features a floor-to-ceiling map of Eurasia and Africa pinpointing Forest City’s “strategic location” amidst Beijing’s snaking OBOR trade routes.

For China the economic and strategic benefit of these projects is not hard to glean, says Ngeow Chow Bing of the University of Malaya’s Institute of China Studies. By constructing deep-sea ports on both sides of the Malaysian peninsula and a railway–the ECRL–that runs between them, Beijing is effectively creating a means of alleviating its heavy reliance on imports through the narrow Strait of Malacca. “For the China side I think the intention is very clear: trying to create a land-bridge so they can bypass the Malacca Straits and Singapore,” Ngeow says.

But as in neighboring countries like Thailand and Indonesia, many are skeptical about whether these projects will benefit any country hosting development. Take the ECRL project. Opponents of Najib claim that it will be constructed by a Chinese state-owned firm at allegedly inflated prices, using mostly Chinese labor and building materials, and funded by soft loans from Chinese state banks. Tony Pua, a parliamentarian from the opposition Democratic Action Party, says this raises the question of whether the ECRL can accurately be described as an “investment” at all. “We do want Chinese investments,” he says, “but the type of Chinese investments that are coming to Malaysia today are either dodgy or in reality are Malaysian-paid-for investments that are not really FDI.” The glut of Beijing-backed port projects has also raised concerns that China may be eyeing them for naval purposes. Ministers in Najib’s government have dismissed claims that the price of the ECRL is inflated.

With national elections looming, the opposition Pakatan Harapan coalition has accused Najib of cozying up to China in a bid to distract attention from the international scandal surrounding the troubled state development fund 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB). Again Dr. Mahathir has been in the forefront. In 2016 the now 92-year-old quit the ruling United Malays National Organization (UMNO)–the keystone of Malaysia’s ruling coalition since independence in 1957–and formed a new Malay nationalist party, which will lead the PH coalition into battle against Najib at the election, due to be held before August 2018.

With Najib under fire for the alleged mishandling of 1MDB, which has chalked up multibillion-dollar losses and is subject to investigations around the world, Mahathir has accused his former protégé of turning to the quick fix of cheap Chinese credit to the detriment of Malaysia’s long-term interests. “The present government is fond of borrowing money without thinking about repayment,” says Mahathir, who denies claims that his own long tenure was marked by cronyism and corruption. “The East Coast Railway is not necessary. … The returns will not be enough to repay the loan.” (Najib has consistently denied taking money from 1MDB or any other public funds).

Adding weight to the claims of opportunism is the fact that Chinese firms have stepped in to buy up pieces of the troubled 1MDB fund. In 2015 China General Nuclear Power acquired Edra Global Energy, a power company belonging to 1MDB. Later that year, Iskandar Waterfront Holdings and the China Railway Engineering Corp. agreed to purchase a 60% stake in the Bandar Malaysia project, another component of 1MDB. (The $1.7 billion deal fell through in May, but seven Chinese state-owned entities are reported to be among the nine firms now bidding for the project.) Last year the Financial Times also reported that China was helping Malaysia repay a $6.5 billion debt to a state-owned petroleum firm in Abu Dhabi.

The controversies over Chinese investment in Malaysia mirror the dilemma facing most of its Southeast Asian neighbors: how to reap benefits from China’s meteoric rise without being sucked into Beijing’s economic orbit. For his own part, Najib has defended his government’s dealing with China. In March he said that the ECRL would be a “game changer” that will contribute 1.5% growth annually to the three states on Malaysia’s east coast. On another occasion he asked, “What’s wrong with us fostering closer ties with China, which is expected to be the biggest economy in 2030?”

Some observers agree. Abdul Majid bin Ahmad Khan, a former ambassador to Beijing who now chairs the Malaysia-China Friendship Association, says that since relations were established with China in 1974 under Najib’s father, Abdul Razak Hussein, Malaysia has tried to maintain good relations with all countries. In the 1970s, he says, Japanese firms came and invested in Malaysia. Then came the so-called Four Tigers: Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan. “Now it’s China’s time,” he says.

Others argue that even if OBOR projects exceed Malaysia’s needs in the short-term, they could lay the basis for sustained future growth. Dr. Ngeow of the University of Malaya says that the ECRL, the Kuantan port project and many other Malaysian OBOR projects were actually conceived years ago but that only Chinese state-owned enterprises had the means and willingness to make them happen. “A lot of this is our own initiative. They come at the right time with the right conditions and the right kind of attitude,” he says. Indeed, the recent influx of Chinese FDI has underpinned a spell of healthy economic growth: Malaysia’s annual GDP growth rate has averaged 5.7% since 2010, with the World Bank predicting a similar rise in 2017.

Still, overdependence on Chinese economic patronage could make Malaysia vulnerable to a sudden economic downturn or policy shift in China. This became clear in March, when Beijing unleashed aggressive measures to clamp down on capital outflows. In Malaysia this arguably contributed to the collapse of the Bandar Malaysia buyout. It also threatened to deprive Forest City of access to its primary target market, leading some to predict that the project will become a giant white elephant.

Yu Runze of Country Garden Pacificview claims that the impact on Forest City so far has been minimal, with just 60 buyers in China–less than 0.5% of the total–asking to cancel their bookings as a result of new capital regulations. “There was some initial impact, but we have been able to balance this, and the project is going smoothly because of this focus on the global market,” he says. “We are in year one of a 20-year project and remain committed to the success of this venture.”

Judging by the crowds at the sales office on a recent Saturday, interest remains healthy. Large groups of foreign visitors trouped through the showroom, buying up souvenirs like dried durian and posing for photos on the manmade beach facing Singapore. At the far end of the beach, where the landscaping petered out amid a few scraggly palm trees and a corrugated iron fence, dredgers were at work creating what will eventually become the project’s second island.

While Forest City may have ridden out the storm this time, concerns about the wisdom of Chinese mega-investments are unlikely to go away. Abdul Majid, the former ambassador, says small countries like Malaysia will each need to learn how to ensure that the flood of OBOR capital serves them as well as it does Beijing. “It’s up to us now,” he says. “The Chinese can deliver a beautiful port, they can deliver a beautiful train–but if the recipient countries don’t take care about the contents, if they’re not prepared for it, they might have an empty port or an empty train.”

Published by Forbes Asia, December 2017