For the Myanmar residents of Chapel Hill, hopes of a return home are tempered by fears of continued ethnic tensions

CHAPEL HILL, North Carolina — It has been 20 years since Lupu last saw his hometown, a small village in the hills of eastern Myanmar. One day in 1997, he and his family fled after the Myanmar military arrived on an operation against ethnic rebels from the Karen National Union, torching homes, killing livestock, and destroying paddy fields. “If you ran, they caught you,” the 42-year-old recalled. “If the police thought you belonged to the KNU, they killed you immediately.”

Two decades on, Lupu finds reminders of his homeland at Transplanting Traditions, a community farm outside the college town of Chapel Hill, North Carolina, that has become a center for the area’s large and growing community of refugees from Myanmar.

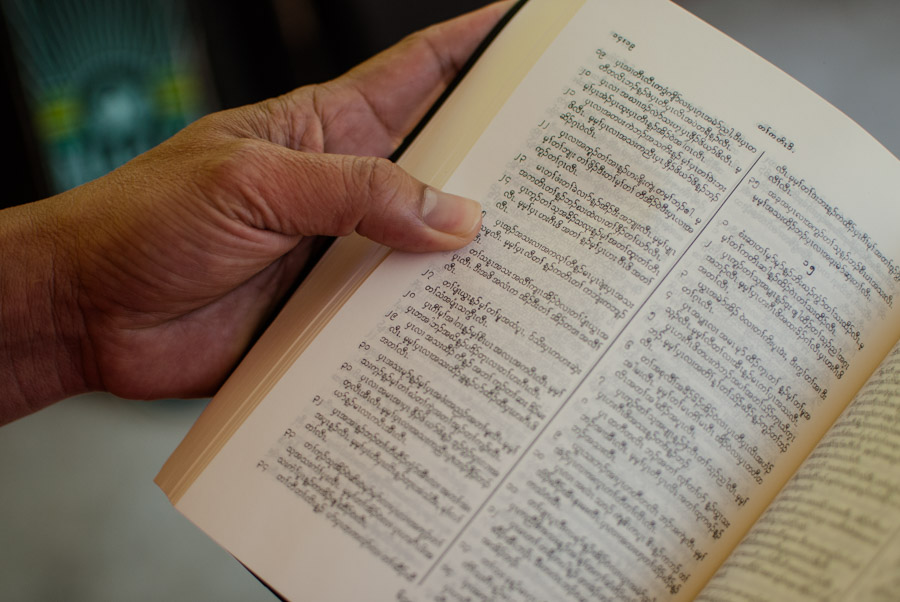

Amid the rows of beans and strawberries, there are hints of the country Lupu left behind. Children play on shaded bamboo platforms; signs are written in Burmese script; and there is even the occasional sour smell of betel nut, Myanmar’s national stimulant of choice. Since its establishment in 2010, the farm has also given Myanmar migrants the space to grow crops from the old country, including snake gourds, roselle leaf, pennywort, lemongrass and fiery chilies. “I feel like I’m back in Burma when I come here,” Lupu said. “In my mind I can see the country that I come from.”

His recollections of Myanmar’s longest-running civil war seem a world away from the sunshine and pollen of North Carolina, nicknamed the Tarheel State, which has become home to a large and growing community of refugees from Myanmar, many of them Karen.

Flicka Bateman, director of the Refugee Support Center in nearby Carrboro, which aids recent arrivals, said that the first Myanmar refugees came to the area in the early 2000s to take up housekeeping jobs at the University of North Carolina, which required no English and provided good benefits. Since then, the presence of community and family networks has attracted more arrivals. “It’s just snowballed,” she said.

North Carolina’s Raleigh-Durham-Chapel Hill “triangle” is now home to one of the largest Karen communities in the U.S., alongside the large communities in St. Paul, Minnesota, and Omaha, Nebraska. There are some 3,000 Karen in the area, in addition to smaller numbers of Chin, Burman, Rohingya and other Myanmar ethnic groups, said Eh Tha Pwee, 46, who heads the Karen Community of North Carolina, a local organization.

Troubled homeland

Despite being far from their troubled homeland, political developments in Myanmar are still followed with great interest, particularly since the election victory of Aung San Suu Kyi and her National League for Democracy in November 2015. Many refugees expressed disappointment that the Nobel laureate had failed to end Myanmar’s wars and heal its deep ethnic divisions. Eh Tha Pwee said that Suu Kyi’s main aim was to “lure” Western governments back to the country with promises of reform, but that she cared little about ethnic minority people. “They want to make Burma as a Burmese country — a pure Burmese country,” he said.

People admitted that a lot has changed since political reforms began in 2011, including the possibility of returning home. Myanmar’s recent opening even prompts comparisons with Vietnam, another war-torn country where, four decades after the communist victory in 1975, former refugees are now returning to fuel an economic resurgence.

According to census data, some 4.25 million people born in Myanmar live abroad, a source of human potential that could one day play an important role in the country’s development. Eh Tha Pwee said that many refugees in North Carolina expressed a desire to contribute in some way to their homeland’s development. After earning a degree in business administration in India, he said his own goal was “to go back to Karen State and establish a business to help Karen people.”

Khin Shwe Aye, a 22-year-old Karen woman who came to the country with her parents as a child in 2001, said she was aware of how lucky she was to reach the U.S., but “definitely” wanted to do something to benefit her homeland. “I know I have to get more education, and experience, and money to go back, to find a way to help them,” she said over coffee in nearby Carrboro, where her mother and stepfather run a small grocery store selling Myanmar specialties like betel nut and pickled tealeaf.

But while Vietnam’s political divisions have faded, Myanmar’s ethnic divisions remain entrenched — even in the U.S. Khin Shwe Aye recalled how in middle school, refugee students would form themselves into separate cliques: Karen, Burman and Chin. “Like, they would separate the ethnic groups,” she said. “We never seemed to be judged as one group.”

Reports from home

This mistrust continues to be fertilized by reports from back home, including allegations that the military is building Burman Buddhist temples and statues of Gen. Aung San — widely considered the architect of independence, and the father of Suu Kyi — throughout Karen State, in a bid to dilute local identity. Several times in interviews around Chapel Hill I heard a quote attributed to Gen. Ket Sein, who reportedly said in 1992: “In 10 years all the Karen will be dead. If you want to see a Karen, you will have to go to a museum in Rangoon.”

Continuing tension has also complicated the return or resettlement of those still in the string of refugee camps along the Thai border. While the situation in Karen State has improved since the KNU’s signing of a Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement in 2015, voluntary repatriations from the camps back into Myanmar have been slow.

Duncan McArthur, the director of the Border Consortium, which coordinates aid to the camps, said that while around 13,000 refugees had returned to Myanmar in the past four years, 98,000 remained. “The democratization and peace-building processes have not built as much confidence amongst refugees as one might have hoped, which is largely because there has not been any troop withdrawals from contested areas,” he said.

Jimmy Shwe, a pastor at the Karen Chapel Hill Seventh Day Adventist Church, who came to the U.S. after more than 20 years in a refugee camp, said that while many refugees in North Carolina wished to return, it would not be easy — and not just because of the conflict. “We’d have to start a new life again, the same as we started a new life in the U.S.,” he said at his home in Chapel Hill.

For now, the Myanmar community in North Carolina is doing its best to put down new roots. Maung Paung is an ethnic Chin farmer who arrived in the U.S. in 2008, after fleeing forced porter duty in the military. Shortly after arriving he underwent surgery to remove a piece of shrapnel from his leg. When asked what first struck him about life in America, he answered with a single Burmese word, lokelatye — “freedom.”

As his wife Cing Neam dished out a picnic lunch from a cooler painted with the blue logo of the Tarheels, the local university football team, Maung Paung spoke about his son, 23, currently at community college. He hoped his son might one day return to Myanmar to help his people. “We have many, many steps to go if you compare Burma and America, Burma and many other countries,” he said. “But I feel there’s been a little bit of change.”

Published in the Nikkei Asian Review, July 8, 2017