The Kings Romans Casino stands out in this remote corner of northwestern Laos, its giant illuminated neon crown towering over a landscape of banana plantations and jungle-clad mountains. Inside, a statue of King Neptune presides over a glitzy lobby, while gamblers sit hunched over nearby tables, throwing down bundles of Thai baht and Chinese yuan on each flip of the cards.

Situated on the Laotian side of the Golden Triangle area, the point where the borders of Thailand, Laos and Myanmar converge, Kings Romans is the centerpiece of the 10,000-hectare Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone, established in 2007 as a joint venture between the Laotian government and the Hong Kong-registered Kings Romans Group.

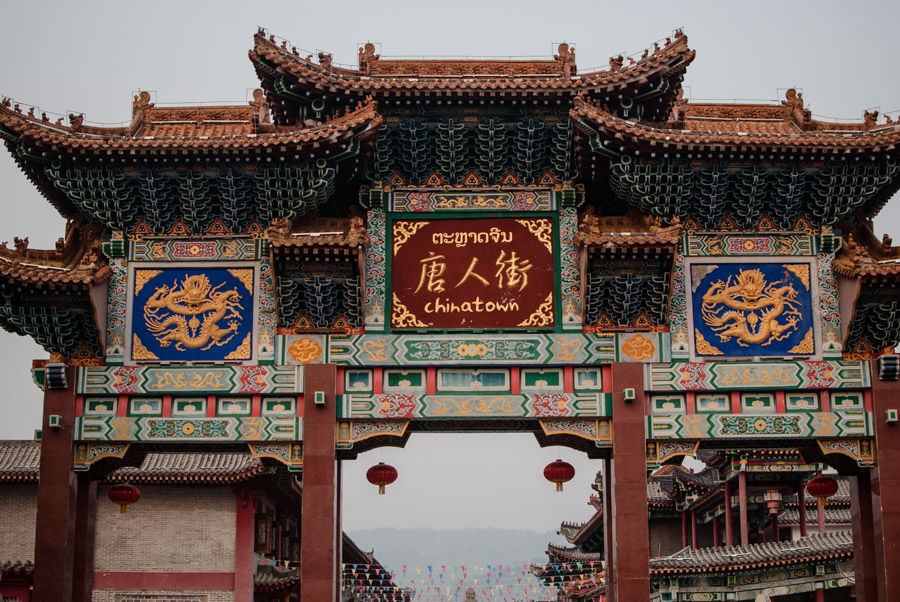

Kings Romans has since spent tens of millions of dollars transforming this remote corner of Bokeo province into a pleasure town for Chinese tourists, a zone of extravagance sprawling along the broad, brown ribbon of the Mekong River. Behind the casino is a special Chinatown district filled with restaurants and so-called “massage parlors.” Boutiques sell trinkets carved from jade, ivory and rare types of wood. Further afield there is a zoo and golf driving range, its parking lot filled with four-wheel drive vehicles. Kings Romans has plans to add an industrial park and international airport, and expects the area will eventually house more than 200,000 people.

Despite being in sleepy Laos, however, the area does not much feel like it. Most of the workers in the GTSEZ are from China or Myanmar, and clocks are turned to Beijing time, an hour ahead of Laos. Most shops refuse to accept payment in local currency, the Laotian kip, and many buildings have been assembled in a kitschy, transplanted style that can only be described as “Forbidden City Lite.” Not far from the casino I met Moe Kyaw, 41, a laborer from Mandalay in central Myanmar who has worked for five years in the SEZ. “Chinese hotels, Chinese money, Chinese construction,” he said, grinning and waving a hand in the direction of the Chinatown. “A small China country!”

Little China

Kings Romans’ activities are opaque, as are the activities of its president Zhao Wei, an entrepreneur from Heilongjiang province in China’s frigid northeast. But Zhao clearly enjoys high-level patronage within the Laotian government. Former President Choummaly Sayasone and former Prime Minister Thongsing Thammavong — who have just been replaced after the expiry of their five-year terms — head a long list of top officials to pay official visits to the GTSEZ, and several former government officials sit on its management committee.

The zone is entirely outside the control of provincial authorities, according to locals and expatriates such as Stuart Ling, a Lao-speaking agricultural consultant based in Bokeo’s provincial capital, Huay Xai. “Even on paper it’s not really part of Laos. It exists as a special zone, a special entity,” he said. Despite being jointly managed by the government and Kings Romans, he added, “it’s not transparent about how much money is paid, about how they divide profits.”

In its overweening ambition and opacity, the GTSEZ encapsulates Beijing’s rapidly-expanding influence in Laos, a landlocked nation which remains one of Southeast Asia’s poorest. Chinese investment has been on the rise here since the early 21st century, when Beijing introduced its “Going Out” policy, encouraging domestic enterprises to invest overseas. Since then, as new highways have breached Laos’s rugged northern mountains, Chinese money has poured into mining, construction, agriculture and hydropower, as well as into 13 SEZs located in strategic parts of the country. By the end of 2013, the cumulative value of these investments had topped $5 billion, making China the largest foreign investor in Laos, along with Vietnam.

Laos has also drawn in thousands of migrants who have created an archipelago of Chinese enclaves across the country’s north. Statistics are hard to come by, but some estimates put the Chinese population in Laos at more than 300,000. Paul Chambers, director of research at the Institute of South East Asian Affairs in Chiang Mai, Thailand, said the combination of Chinese migration, investment and aggressive diplomacy amounted to a “new form of neo-colonialism” in Laos. “Northern Laos is sort of becoming a neo-China — there are so many Chinese coming in,” he told the Nikkei Asian Review.

Booming capital

The mainland presence can also be seen and felt in Vientiane, home to a large Chinese community centered around the Chinese-funded Sanjiang Market, which opened in the western part of the city in 2007. “When they came to invest, here was a backwater,” said Huang Zhitang, 70, a Taiwanese cab driver who works the Sanjiang area. “Now in Sanjiang almost every shop makes money.”

Entering the area is like slipping imperceptibly into a large town in Yunnan, the southern Chinese province that borders Laos. Mandarin is the lingua franca. The market is packed to bursting with Chinese goods, from karaoke machines to baijiu firewater, while travel agents hawk cheap flights and bus tickets back to China.

This rising influence has not been without controversy. Critics say many Chinese investments, especially dams and large infrastructure projects, have proceeded with little concern for their social or environmental costs. In 2014, Laotian villagers living within the GTSEZ held protests against land seizures and blocked Chinese developers from surveying land earmarked for an airport. Representatives of Kings Romans Group were unavailable for interviews, but a casino manager who spoke on condition of anonymity said the airport project had since been postponed. Similar stumbles have accompanied a $1.6 billion property development in the That Luang Marsh area in Vientiane and the long-delayed $7 billion railway link between Kunming, the capital of Yunnan, and Vientiane.

Of more concern for some is the growing view that China is prising Laos away from its traditional communist ally Vietnam, which has intimate ties to the ruling Lao People’s Revolutionary Party dating back to its long struggle to overthrow the U.S.-backed monarchy in the 1960s and 1970s. Where once Vietnam was the “older brother,” a Vientiane-based Asian diplomat said, “now things have changed. China is the older brother, and Vietnam is maybe the second brother.”

According to some analysts, worries about China’s rising influence were behind the leadership changes enacted at the LPRP’s 10th National Congress in January. Emerging from the conclave as the new secretary-general was 78-year-old Boungnang Vorachit, who, like his predecessor Choummaly Sayasone, is a veteran of the revolutionary struggle with close ties to Vietnam.

The congress also promoted the offspring of several notable comrades into the LPRP’s 11-member Politburo, and cast out Deputy Prime Minister Somsavat Lengsavad, an ethnic Chinese party grandee who is said to have played a key role in brokering key Chinese investments, including the GTSEZ. Boungnang was further elevated on April 20 when the unicameral National Assembly elected him the country’s new president and named foreign minister Thongloun Sisoulith as prime minister.

In early September, U.S. President Barack Obama will visit Laos for the annual summit of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, becoming the first U.S. leader to visit the country. Many U.S. officials believe that with a new leadership in charge in Vientiane, the time is ripe for an expansion of ties with Laos. In November, Deputy National Security Advisor Ben Rhodes told an audience in Washington that “there is a sense of potential” in the relationship with Laos “for the first time in a long time.”

Chinese influence

But one specialist with close knowledge of the Laotian leadership said the recent changes were unlikely to result in a strong backlash against the Chinese presence. Having jettisoned most of its ideological baggage and embraced a sort of commodity-based crony capitalism, the party continues to favor Chinese investment, which was strongly encouraged by Thongsing during his premiership. The party’s main concern is about the appearance of corruption that has dogged some recent Chinese investments, which the Asian diplomat in Vientiane alleged have served as cover for the transfer of “black money” out of mainland China.

“The Party leaders in Laos are mostly interested in getting cash without strings, be it in the form of grants or zero interest loans or big brown paper bags,” the specialist said. “They don’t really care about the provenance as long as they can pocket a large sum for their families and another large chunk for the party coffers.”

While Vietnam’s economic and political influence will remain strong, the coming years are likely to see the continuing expansion of China’s footprint in Laos through a combination of entrenched personal relationships, geographic proximity, and the sheer gravitational weight of China’s economy, which is some 862 times bigger than that of Laos. “They’ll build up their connections, and it’ll probably be a bit like the Tibetanization of Laos,” said Ling, the Bokeo-based consultant. “I don’t think [the country] will be able to resist it.”

Published by Nikkei Asian Review, April 21, 2016