With connectivity boom, Cambodia’s political battles shift online

by Sebastian Strangio on Dec 28, 2015 • 9:44 am No Comments-

Cambodia's Prime Minister Hun Sen poses for a selfie with his wife Bun Rany during Khmer New Year celebrations. This photo was posted on his Facebook page on April 14, 2016.

Cambodia's Prime Minister Hun Sen poses for a selfie with his wife Bun Rany during Khmer New Year celebrations. This photo was posted on his Facebook page on April 14, 2016.

-

Thy Sovantha, 20, has amassed nearly a million Facebook followers by posting mix of fashion selfies and news about politics and social issues. This photo, posted on November 30, received more than 83,000 likes and 1,400 comments.

Thy Sovantha, 20, has amassed nearly a million Facebook followers by posting mix of fashion selfies and news about politics and social issues. This photo, posted on November 30, received more than 83,000 likes and 1,400 comments.

-

Hun Sen has embraced Facebook with enthusiasm, amassing 2.6m followers as of March 2016. This photo was posted on February 28.

Hun Sen has embraced Facebook with enthusiasm, amassing 2.6m followers as of March 2016. This photo was posted on February 28.

-

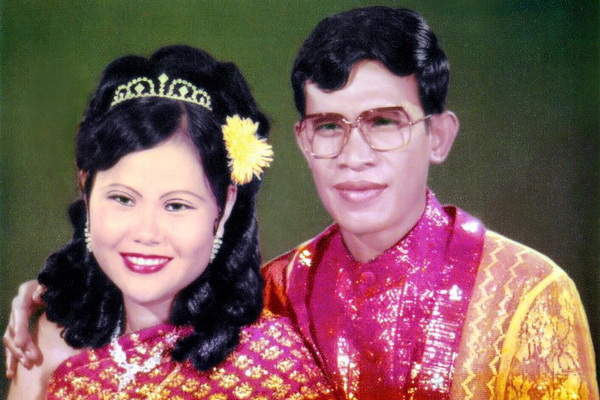

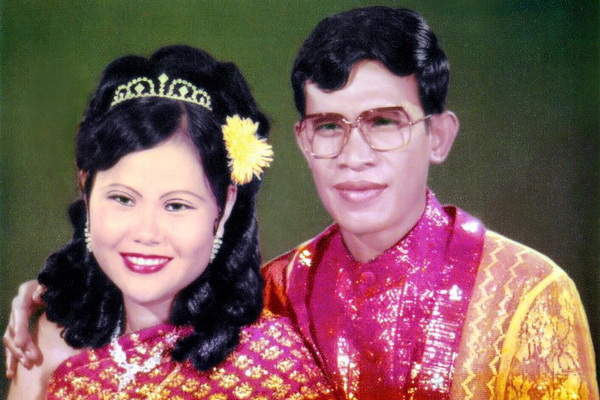

This image posted on December 14 shows Hun Sen and his wife Bun Rany in traditional wedding regalia, c. 1988.

This image posted on December 14 shows Hun Sen and his wife Bun Rany in traditional wedding regalia, c. 1988.

-

This photo posted on Hun Sen's Facebook page shows the prime minister greeting supporters in 1996.

This photo posted on Hun Sen's Facebook page shows the prime minister greeting supporters in 1996.

-

In a photo posted on his Facebook on November 29, Cambodia’s Prime Minister Hun Sen poses with two granddaughters.

In a photo posted on his Facebook on November 29, Cambodia’s Prime Minister Hun Sen poses with two granddaughters.

PHNOM PENH — In September 2015, a Facebook page bearing the name of Prime Minister Hun Sen notched up its millionth “like.” Until then, the long-serving Cambodian leader had denied ever using social media, making fun of political rivals, like opposition leader Sam Rainsy, who were active online. But with its following now in seven figures, Hun Sen finally not only admitted the page was his but began to promote it.

“We started it first as a test,” Sok Eysan, a spokesman for the ruling Cambodian People’s Party, told local media. “Then we saw that it has attracted popularity and is very popular among citizens, so we made it official to widen communication between top leaders and the people.”

Since then Cambodia’s prime minister has enthusiastically embraced Facebook. His page, which features everything from live-streamed speeches and ribbon-cuttings to photos from Hun Sen’s 31 years in power, is now one of the fastest growing in Cambodia in popularity terms. In the past three months it has leapt to 1.55 million fans, making it the country’s seventh most popular page, according to Socialbakers, a social media tracking site. Rainsy, the premier’s long-time rival, sits in third place, with nearly 2 million followers, but at the current rate, Hun Sen should out-“like” him sometime in the next year.

Hun Sen’s dive into the digital world reflects the ruling CPP’s broader campaign to extend its presence online following a sharp fall in its popularity at the last national election in 2013. Confident of victory, the party saw its majority plunge from 90 seats in the 123-seat National Assembly to just 68. The main beneficiary was Rainsy’s Cambodia National Rescue Party, which cleverly used social media platforms like Facebook and YouTube to circumvent the CPP’s tight control of the press and disseminate information about problems like land-grabs, police violence, and corruption.

“It was a blessing for the opposition to have Facebook at the time,” said Ou Ritthy, a blogger who runs Politikoffee, a weekly political discussion group. “The opposition had no access to other media.” Ritthy said that the CNRP’s social media successes served to jolt Hun Sen and his government into the digital age. “They want to attract new voters,” he said, “and a lot of young people have started to use Facebook.”

Internet boom

The election took place in the midst of Cambodia’s recent Internet boom. Since 2010 the number of Cambodians online has leapt from 320,000 to more than 5 million — around a third of the population — according to official government figures. As in neighboring countries like Myanmar, this has been fueled by strong economic growth and the increasing availability of cheap, web-enabled smartphones.

A report issued in November by the Asia Foundation and the Phnom Penh-based Open Institute found that some 40% of Cambodians now own a smartphone, twice the number as in 2013. More than 98% of those accessing the Internet do so from mobile devices.

“There’s a lot changing. Just the pace of the adoption of the smartphone is mind-boggling,” said Silas Everett, the Asia Foundation’s country representative for Cambodia.

The report also found that the Internet has become the country’s second-most important source of information, after television. “People generally come online to socialize and meet friends and things like that, but as they start getting on Facebook, they want to get information about news and events. It’s a dynamic process of engagement,” Everett said.

With an estimated 3 million Cambodians now on Facebook, and many more expected to log on in coming years, social media looms as a crucial political arena ahead of local elections in 2017 and crunch national polls the following year. After its shock losses in 2013, the Cambodian government made a concerted push to counter the CNRP’s strong online presence. Politicians, ministries, and other government bodies were instructed to open Facebook pages. (Even the CPP’s Heng Samrin, the octogenarian president of the National Assembly, has a profile, boasting a more modest 13,436 “likes”). In June, according to a Reuters report, the government held mandatory classes for 400 heads of schools in Phnom Penh, in which they were shown how to open Facebook accounts and defend the government from negative messages online.

The CPP’s cyber-strategy is best encapsulated by Hun Sen’s Facebook page, which has been used both to promote government achievements and to craft a softer public image for the pugnacious leader. Between information about bridge-openings and public speeches, the page has featured old family photos of Hun Sen with his wife Bun Rany and their children; other posts have shown a youthful Hun Sen playing sports with fellow politicians during the 1980s. “He is trying to show the public that he’s a good leader, a good father, a good husband,” said Ou Ritthy.

Phay Siphan, a spokesman for the Council of Ministers, Cambodia’s cabinet, said Facebook offered Hun Sen and other leaders the benefit of “two-way communication”. “The prime minister learns from his own people what the people want and what the people don’t like,” he said. “It’s not targeted to the election, it’s targeted to better serve the people.”

New way to engage

It is true that social media has given people a new way of putting pressure on public officials. In July, Sok Bun, a Phnom Penh property tycoon, was caught on a restaurant’s CCTV camera savagely beating an entertainer and former TV presenter. The footage was leaked online and quickly went viral. In the face of rising public outrage, Hun Sen condemned the attack and the tycoon was arrested.

Thy Sovantha, a prominent Facebook user who helped disseminate news of the beating, said that in years past, a man like Sok Bun would have escaped punishment. “Before, everyone was afraid of rich people, or oknha [tycoons], or the government,” she said.

At the age of 20, Sovantha is already the doyenne of Cambodia’s social media scene. Her Facebook page, a stream of fashion selfies and commentary on issues such as anti-government protests, rural poverty, and border disputes with Vietnam, now counts just under a million fans — more than most leading politicians.

Many of Sovantha’s fans signed up in the run-up to the 2013 election, when the high-school student started posting opposition news alongside glamorous selfies and photos. Unlike TV, which is tightly controlled by the government, Sovantha noted in an interview that the Internet has given Cambodians a way to make direct demands of their leaders. “Facebook is very important. It’s like a mirror for our government and for our people,” she said.

Ritthy agrees that the Internet and digital media has great potential. So far, however, it has had limited effect on the quality of the country’s political debate. He pointed out that Cambodian Internet users are much more likely to “like” individual politicians than their parties, reflecting the continuing precedence of personality over platform in Cambodian politics. Supporters of both parties, meanwhile, have used the Internet to spread old rumors, insults, prejudice, and misinformation.

Old habits die hard

To a large extent, Cambodia’s old political battles have simply moved online. As the “culture of dialogue” established by Hun Sen and Rainsy collapsed earlier this year, the two men have used Facebook to continue their two-decade-long political jousting. In mid-November, after the government activated an old arrest warrant against Rainsy, effectively forcing him into self-exile, he made a Facebook post branding Hun Sen a “dictator” and comparing himself to Aung San Suu Kyi, whose opposition party had just won a landslide election victory in Myanmar. Hun Sen responded by live-streaming a speech on his Facebook page in which he called Rainsy “the son of a traitor to the nation,” referring to his father’s opposition to Prince Norodom Sihanouk.

“They face off,” Ou Ritthy said of the dueling Facebook pages. “They compete not just in terms of fans and followers — their content is attacking each other.” In other words: business as usual for Cambodian politics.

Ritthy said that while the quality of online debate was slowly improving, Facebook and other digital platforms offered no short-cut to lasting political change — something which would need to begin offline. “It’s just a platform,” he said, “but it needs content.”

Published by the Nikkei Asian Review, December 25, 2015