YANGON—With a few deft strokes of Beruma’s pen, a jowly likeness appears on the blank page: a caricature of Senior Gen. Than Shwe, Myanmar’s former dictator. A few more lines and his successor, President Thein Sein, materializes. A slight, bespectacled man, he looks somewhat nervous, eyes bulging comically.

Beruma, one of Myanmar’s emerging political cartoonists, picked up his pen in 2007, when mass protests led by Buddhist monks were quelled with ruthless force by the military. “I thought, how could I go against the junta?” he recalled. “I was looking for a weapon. And I found this weapon.”

Following the abolition of pre-publication censorship in 2012, the softly spoken 33-year-old — real name Wunna Soe — enjoys a freedom that his predecessors never did. His cartoons, published in the Democratic Voice of Burma, The Irrawaddy news magazine and directly on Facebook, depict child soldiers, illegal logging, military politics — topics that were previously off-limits.

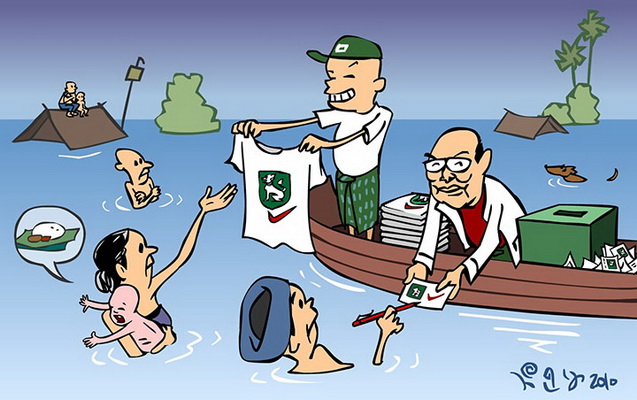

One recent effort shows a tight-lipped Thein Sein rowing through rising floodwaters, handing out T-shirts on behalf of his Union Solidarity and Development Party to flailing flood victims.

Like the old Soviet-bloc jokes that chipped away at the pretensions of “actually existing” socialism — “You pretend to pay us, we pretend to work” — Myanmar’s cartoonists have, for decades, used satire to skewer homegrown dictators and tyrants. But under censorship, Beruma said, “Our thinking wasn’t free. Our mindset wasn’t free until now.”

Simple, humorous and instantly absorbable, political cartoons today represent the sharp satirical edge of a press that has been reinvigorated by political reform. With the end of direct censorship, cartoons are enjoying a renaissance in Myanmar, fueled by social media platforms that have given artists such as Beruma access to a larger audience than ever before.

As the country approaches landmark elections on Nov. 8, a growing fraternity of cartoonists stands ready to pour humor and ridicule upon those in power. “They are as bold as ever,” said Thiha Saw, a veteran journalist and president of the Myanmar Journalists Association.

Political cartooning has a long history in Myanmar. A seminal character in that history was Ba Gyan (1902-1953). Like his contemporary Herge, the Belgian creator of Tintin and his dog Snowy, Ba Gyan infused his work with reflections on his country’s political evolution. He pioneered newspaper cartoons and produced Myanmar’s first animated short film in 1935. In his final years, Ba Gyan held an annual cartoon exhibition outside his home in downtown Yangon, a festival revived by his successors in 2010 on a street that now bears his name.

Despite the passage of time, Ba Gyan’s illustrations addressed similar social and political issues facing the current generation. “His political cartoons are still relevant, even today,” Thiha Saw said.

After the 1962 military coup, the authorities instituted censorship and clamped down on political expression. Maung Maung Fountain, 47, who contributes cartoons to The Irrawaddy and other local journals, took up his craft around the time of the 1988 student protests, which prompted a campaign of fierce repression by the military. “Cartoonists drew cartoons to stimulate the movement, but we couldn’t use our real names,” he said. “The government was squeezing everything.”

Self-censorship de rigueur

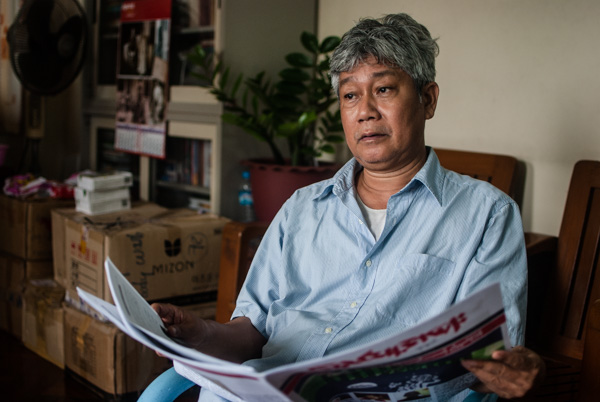

Myanmar’s most famous living cartoonist, Aw Pi Kyeh, has witnessed the evolution of the media landscape over more than three decades. “Before 2012, when we were thinking of ideas — before we drew — we needed to censor ourselves,” the 57-year-old said. “It was a very bad habit.”

Aw Pi Kyeh — his real name is Win Naing, and his friends and peers call him A.P.K. — lives on the third floor of a musty apartment block in the Yangon suburbs. He draws on a small draughtsman’s desk, crammed between a bed and a shelf filled with art books he bought while completing a master’s degree at Harvard University in 2002-2003. Shoeboxes hold his large collection of fountain pens and precious tools, also procured abroad.

Like most of his peers, the Mandalay-born Aw Pi Kyeh, whose pen name means “loudspeaker,” is self-taught. He took up cartooning seriously after arriving in Yangon to pursue an engineering degree in 1975. Those were turbulent days in student politics. The year before, protests erupted when then-dictator Gen. Ne Win refused to accord a state funeral to U Thant, the recently deceased secretary-general of the United Nations. After a tumultuous week, the military responded with lethal force, killing more than 100 students.

Aw Pi Kyeh’s early cartoons dealt with issues of student life, but he soon gravitated to politics. “I needed to carry some of the load for my country,” he explained. But with censors vetting every publication for anything deemed remotely subversive, the system tested cartoonists’ reserves of metaphor and suggestion. Aw Pi Kyeh estimates that more than 300 of his cartoons were nixed by the censors over the years.

The vetting process involved submitting newspapers and journals to a censorship office before publication; the office then spiked anything it felt would be offensive. But Aw Pi Kyeh was, nonetheless, able to get many subtle messages through, laying down some symbolic markers and then letting a knowing audience fill in the blanks.

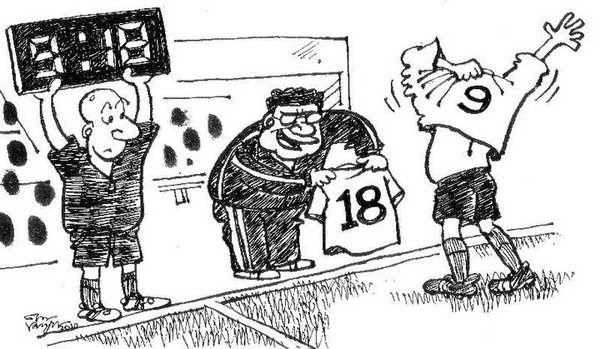

One of his simplest and most famous images appeared ahead of the widely criticized 2010 election. It depicts a soccer player coming off the field to be substituted, but instead of being replaced by another player, he merely switches shirts — just like the generals reinventing themselves as civilian politicians. Nobody in Myanmar needed the joke explained to them.

Aw Pi Kyeh said the best cartoons tap the unspoken assumptions lurking beneath the crust of daily life. Hence, the reason for his nom de plume: “A loudspeaker has no voice, it only amplifies the voice. The artist or cartoonist has no voice, he only reflects the public voice.”

Pressure persists

In Aw Pi Kyeh’s view, Myanmar’s young cartoonists, for all their technical skill, have yet to develop the searing touch of the old masters, although he is optimistic. “They begin to walk on free ground, but their feet are not strong enough,” he said. “But after two or three or four years, they will run.”

Of course, there are still limits on how far Myanmar’s cartoonists can go. After a police crackdown on student protests in March, Beruma produced a cartoon depicting the goons who attacked protesters with slingshots. He said he received a threatening message from an official on Facebook. “This year there’s been more pressure on cartoonists,” he said.

In March, The Myanmar Times, the country’s only daily newspaper with foreign ownership, was forced to apologize after publishing a cartoon by Htoo Chit, which suggested a link between Myanmar’s armed forces and evictions of farmers. “This cartoon was inappropriate and not in good taste,” Chief Executive Tony Child wrote on the newspaper’s website.

Another challenge that cartoonists face is purely practical: It is nearly impossible to live off their trade, with publications paying as little as 5,000 kyat ($3.87) per cartoon. “Very few people can make a living as a cartoonist,” said Maung Maung Fountain, a bachelor who runs a grocery store to supplement his income. “It’s like my hobby, but I can live with that.” Even A.P.K., the doyen of the industry, earns his living doing graphic design work and commissions for nongovernmental organizations.

Despite such obstacles, Myanmar’s most subversive art form has never had such fertile soil. Indeed, it seems almost tailor-made for the country’s new age of social media: humorous, instantly digestible, “shareable” at the click of a button.

“Cartoons take up just a little space,” Maung Maung Fountain said, “and they tell so much.”

Published by Nikkei Asian Review, October 2, 2015