YANGON — It says a lot about Myanmar’s tech scene that one of its pioneers is still in his 20s.

Htoo Myint Naung was just 18 in 2004, when he built his country’s first mobile phone app — a simple program for sending text messages in the Burmese language. After graduation, when most of his classmates headed for greener tech pastures in Singapore or the U.S., he chose to stick it out in Myanmar, a country then languishing in a self-imposed digital dark age.

“I’m the only one who stayed behind and kept doing this kind of stuff,” he said. “I saw a lot of potential in Myanmar.” In 2006 Naung founded his software company Technomation and began developing apps for the tiny local market. It would take almost a decade for his gamble to start to pay off.

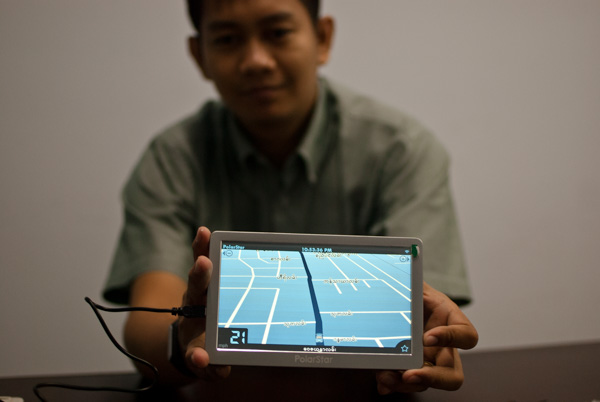

Now, thanks to a sudden connectivity boom and a rapidly developing cellphone network, Myanmar has become an improbable frontier for tech startups. In 2011, Naung plowed all his savings into developing a Myanmar-specific GPS navigation unit called PolarStar. It took him two years to draw the maps, build the software, and line up manufacturers in China. When it launched in 2013, the PolarStar navigation units, which were available in five models costing between $85 and $200, were an instant success. Technomation has since sold “a few thousand” of the sleek GPS units, which guide drivers around town with Burmese language directions. “Suddenly there’s a big market in Myanmar,” Naung said.

Speedy change

Just five years ago, Myanmar’s tech sector was almost a contradiction in terms. Internet access was expensive, and so sluggish that it was sometimes quicker to physically transport files across town than to send them digitally. Cellphone subscriptions, tightly controlled by the paranoid military junta then ruling the country, cost $3,000 apiece. Owning one put you in “a different class,” Myint Naung recalled.

Then, in 2011, the government of President Thein Sein took office and initiated political and economic reforms geared at ending Myanmar’s international isolation. The government awarded the Norwegian telecoms giant Telenor and Qatar-based Ooredoo 15-year licenses to expand the country’s limited telecoms network and boost internet penetration. Last year, the two companies flooded the market with cheap SIM cards.

The sudden availability of 3G data and cheap smartphone handsets — some costing as little as $30 — means that most of Myanmar’s 53 million people are experiencing the internet for the first time on mobile devices. “This is really the first time that a country of this size has come online so quickly and gone straight to smartphones,” said David Madden, the Australian founder of Phandeeyar, a collaborative tech hub in downtown Yangon. “Myanmar may well set some records for speed of penetration.”

By March this year, the country’s mobile penetration rate had topped 50%, according to Myanmar’s Ministry of Communications and Information Technology, up from around 10% at the end of 2013. So far, Myanmar’s relatively young population has been quick to embrace social media apps like Facebook and Viber, which have each attracted millions of local users. Facebook now has an estimated 3.8 million users in the country. Viber, the most popular messaging app, claims more than 5 million users.

Drawn home

The sudden appearance of a booming consumer tech market has also drawn dozens of young Myanmar entrepreneurs home from overseas, hoping their knowledge of local conditions can help them carve out a space alongside the big players. One is Myo Myint Kyaw, who studied computer science at Middlesex University in the U.K. before returning to Myanmar in 2012 to found RevoTech, a software and web design company. RevoTech is based in a musty, sixth-floor apartment in central Yangon where photos of Steve Jobs and Mark Zuckerberg share the walls with whirring air-conditioners. “Apple is like a religion for us,” he said.

Last year RevoTech released Phew, its first proprietary Android app, which teaches children the Burmese script; now it has plans to create an entire suite of educational apps. “Before I couldn’t imagine coming back and starting my own firm in Myanmar,” Myint Kyaw said. “I always wanted to do my own business, but this wasn’t a plan when I went [overseas].”

Myanmar’s tech sector still faces some stiff challenges. Developers have to deal with competing and incompatible standards for displaying the Burmese script. Power cuts remain frequent and the cost of internet is prohibitively high. It can also be hard for companies to find skilled graduates fluent in the latest coding languages, especially when better pay is still available in places like Singapore. “That’s not just in IT, that’s everywhere,” said Ko Revi, a long-time software developer and founder of DevLab Yangon, the city’s first collaborative tech hub. “The training schools don’t provide enough usable talent.”

But the biggest hurdle, many tech entrepreneurs say, is how to monetize their products. Less than 10% of Myanmar’s population possesses a bank account, a fact that has inhibited development of online payment systems. As Htoo Myint Naung of Technomation put it, “there’s no way of getting money through the banking system to the developers.”

Previously, Naung distributed his apps directly to phone shops on encrypted USB sticks. Now he is ready to launch his next project: an all-Myanmar app store. When Technomation’s app store launches — the plan is for this to happen later this year — it will allow customers to make purchases with prepaid scratch cards. With the impending extension of app stores like Google Play into Myanmar, he admits it’s a risky gambit. “There must be something to fill in the gap,” he said. “I’m trying to do it.”

Investor interest

Despite the challenges, overseas tech investors are showing strong faith in Myanmar’s potential. MySquar, a Singapore-based company behind the local chat app MyChat, claims it has attracted 800,000 local users since launching the beta version of the app in August. The company’s founders are planning to list MySquar on the London Stock Exchange’s Alternative Investment Market by the end of June, seeking $2.5 million in funding on a $25 million valuation.

Daniel Campbell, MySquar’s general manager, says the company and its investors are confident their product — honed over months of market testing in Myanmar — can coexist with dominant rivals like Facebook and Viber. “The more unique aspects we find, the more we can differentiate and change our products to suit Myanmar,” Campbell said.

Taking a similar local approach is Myanmar CarsDB, the country’s leading classified advertising site for cars. Not long after Myanmar’s vehicle import system was deregulated in 2011, Wai Yan Lin, 31, returned to Myanmar from Singapore and founded Rebbiz, which set up Myanmar CarsDB and other online classified services. Lin says he was lured by the prospect of being able to fill an important niche: “The country was opening up and the people here were trying to change, so I thought, why not?” Myanmar CarsDB now counts 80,000 active web users, plus 30,000 more on the site’s Android app. “It’s at a bit of an early stage,” Lin said, “but I think the time will come when it takes off.”

Others, like David Madden of Phandeeyar, are hoping that the connectivity boom can be harnessed for socially-progressive ends. In early 2014, Madden founded Code for Change Myanmar, a new-technology initiative, and organized the country’s first “hackathons” — tech cram sessions in which attendees are tasked with finding solutions to various civic challenges within a short space of time. Struck by the “huge” amount of energy, enthusiasm and talent he saw, Madden went on to establish Phandeeyar, a collaborative tech space or “hub” modeled on similar facilities elsewhere in the developing world.

The aim of Phandeeyar, housed in a converted office with sweeping views over the Yangon River, is to function as a permanent base for tech-related events, hackathons, and other tech-civil society collaborations.

“We’ve seen the tremendous impact that technology’s made in other countries. But one of the challenges is that because Myanmar was largely cut off from large parts of the world for so long, it’s not necessarily going to happen automatically,” Madden said on a recent evening, as local tech-heads gathered for a live, night-time streaming of the Google I/O development conference from San Francisco. “The idea was, let’s create a space that can try to harness the potential of this connectivity revolution.”

Published by Nikkei Asian Review, June 22, 2015.