PHNOM PENH — The recent death of Chea Sim, a key figure in Cambodia’s politics since the fall of the communist Khmer Rouge regime in 1979, has put a spotlight on the future of Prime Minister Hun Sen, his long-time ally and one of the world’s longest serving national leaders. Chea Sim died on June 8 at the age of 82. For more than three decades, he had been a pillar of the country’s ruling establishment, serving for years as president of the formerly communist Cambodian People’s Party, as well as president of the country’s senate.

As old comrades and colleagues paid their respects at Chea Sim’s villa in Phnom Penh this week, CPP spokesman Sok Eysan paid tribute to the party stalwart, telling local media that he “used one of his hands to stop the Khmer Rouge genocide that killed the people from happening again, while using his other hand to hold a hoe and a plow to lead the people to rebuild the country.” Hun Sen declared June 19 an official day of mourning, when flags will fly at one-third mast and Chea Sim will be cremated in a ceremony near the Wat Botum Buddhist temple in Phnom Penh.

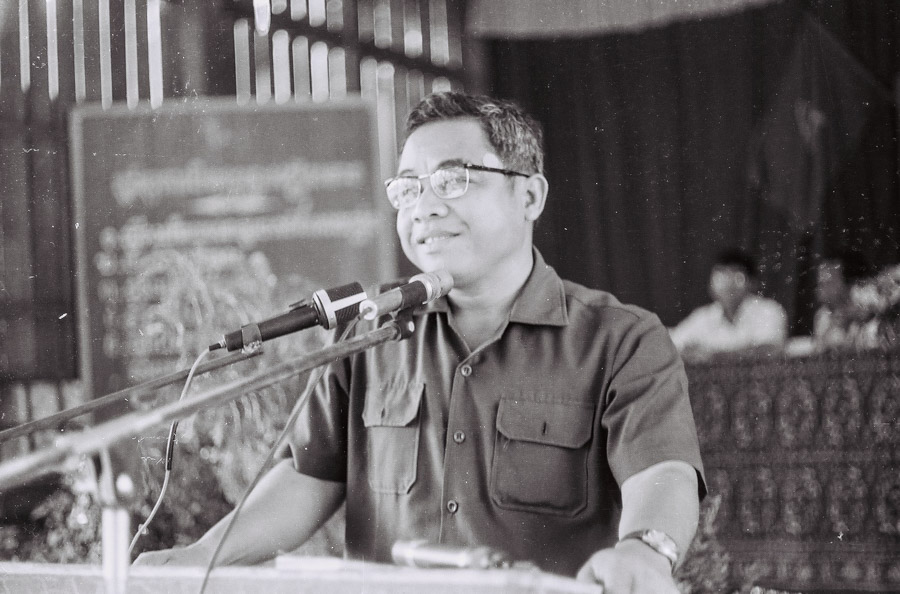

Though little known outside Cambodia, Chea Sim was a crucial figure in his country’s politics following the overthrow of the Khmer Rouge regime in 1979. Along with Hun Sen and 81-year-old National Assembly President Heng Samrin, he dominated the communist regime that controlled Cambodia throughout the 1980s, and maintained a prominent position in the multi-party system established after the end of the Cold War.

Born in 1932 in a rural area of Svay Rieng province near Cambodia’s border with Vietnam, Chea Sim studied at a Buddhist pagoda and began his political career as an organizer among the monks. In 1952 he joined the anti-colonial Issarak movement, and later the Cambodian communist party. Chea Sim continued to serve the communists — also known as the Khmer Rouge — after they seized power in April 1975, establishing a murderous slave state that would eventually lead to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Cambodians. After rising to the post of district party secretary in the country’s Eastern Zone, he fled to Vietnam in mid-1978 to escape vicious political purges.

Chea Sim served as deputy chairman of the Kampuchean United Front for National Salvation, established by the Vietnamese communists in December 1978 to support their coming offensive against the Khmer Rouge regime, which the Vietnamese army drove out of power in January 1979. In the regime that replaced it, he became interior minister, drawing on his Khmer Rouge-era connections to carve out a prominent position.

Throughout the 1980s Chea Sim was a leading member of the Phnom Penh government, in firm control of the repressive state security apparatus. In his 2004 book “Cambodia After the Khmer Rouge,” Evan Gottesman described Chea Sim as “an old-fashioned Cambodian politician who understood how to nurture a patronage system and how to inspire loyalty in his followers.” But as time went by his power was gradually eclipsed by that of Hun Sen, a political prodigy 20 years his junior, who was appointed prime minister in 1985 and played a key role in international peace talks seeking an end to Cambodia’s long civil war. Unlike the mutable Hun Sen, Chea Sim was less able to adapt to the more open political system established after the signing of the Paris peace accords that ended the civil war in October 1991. After suffering a stroke in October 2000, and increasingly out-maneuvered by the wily and powerful Hun Sen, Chea Sim gradually withdrew from official duties.

Serious challenges

Chea Sim leaves behind a party that faces serious challenges as Cambodia moves toward national elections in 2018. In the last poll in 2013, the CPP saw its share of National Assembly seats slashed from 90 to 68 of the total of 123 — its worst electoral result since 1998. The Cambodia National Rescue Party, led by Hun Sen’s nemesis Sam Rainsy, deftly capitalized on rising popular discontent about land-grabs, ballooning income inequality and everyday corruption, which continue to plague the country despite political stability and impressive economic growth over the past two decades.

After the shock election result, Hun Sen promised sweeping reforms. The government has since offered wage hikes to teachers and soldiers, and reshuffled its cabinet to include a number of younger, more able technocrats. Two years on, however, the top leadership of the CPP remains mostly unchanged. In January, the 62-year-old Hun Sen marked his 30th year in power; many of his key aides and ministers have occupied senior posts since the 1990s, if not earlier. Before Chea Sim’s death last week, six of the 10 highest-ranking members of the CPP’s politburo, in theory the party’s key decision-making body, were founding members of the movement that helped to overthrow the Khmer Rouge in 1979.

At the same time, old political problems persist: Illegal or semi-legal logging continues to devastate Cambodia’s forests, and land-grabs by powerful people continue to make headlines. The government has also intensified its persecution of activists offering alternatives: The past two years have seen a series of violent crackdowns on demonstrations (when they have been permitted to take place) as well as the jailing of opposition figures and land rights activists.

As a result, the party finds itself out of touch with Cambodia’s young population, nearly two-thirds of which is below the age of 30, according to the United Nations. “The greatest challenge for the CPP will be to reinvent itself into a party of the present,” said Ou Virak, who heads the Future Forum, a Phnom Penh-based policy institute. “If you compare [party leaders] to the voting population there’s a disconnect there — the majority are not even from the same generation.”

“The greatest challenge for the CPP will be to reinvent itself into a party of the present”

Given his long illness, the death of the CPP’s long-time figurehead is unlikely to alter the internal dynamics of the party fundamentally. On June 20, the CPP will convene a special congress which is expected to appoint Hun Sen as the new party president, while current secretary-general Say Chhum has already taken over the post of senate president. But observers say the passing of one of Hun Sen’s main internal rivals may give him greater leverage to advance promised reforms and speed up the generational transition within the party. While Chea Sim’s hard power has long been in decline, Ou Virak said, the CPP president played an important role as a party elder, helping to defuse personal disagreements and intra-party turf wars. Ou Virak said this helped to maintain internal stability, but also prevented a necessary clean-out of ageing officials and hangers-on.

Ok Serei Sopheak, a development consultant who served as a political adviser to the CPP in the 1990s, said that with Chea Sim off the scene, Hun Sen will likely have more of a free hand to ease out party veterans and make the deep changes necessary to win back public support while maintaining the stability necessary for continued economic growth. “By becoming the president of the party he will probably have more freedom to introduce reform policy, to promote younger reform-minded people into key institutions,” Sopheak said.

The wider question, however, remains whether a greater reliance on Hun Sen, which many critics see as the root of the country’s problems to begin with, is really the solution to the party’s legitimacy deficit. Sopheak said that if Hun Sen now had more freedom than ever to make the right decisions, the reverse was also true. “If he fails,” he said, “it will only be himself that is responsible.”

Published by Nikkei Asian Review, June 15, 2015