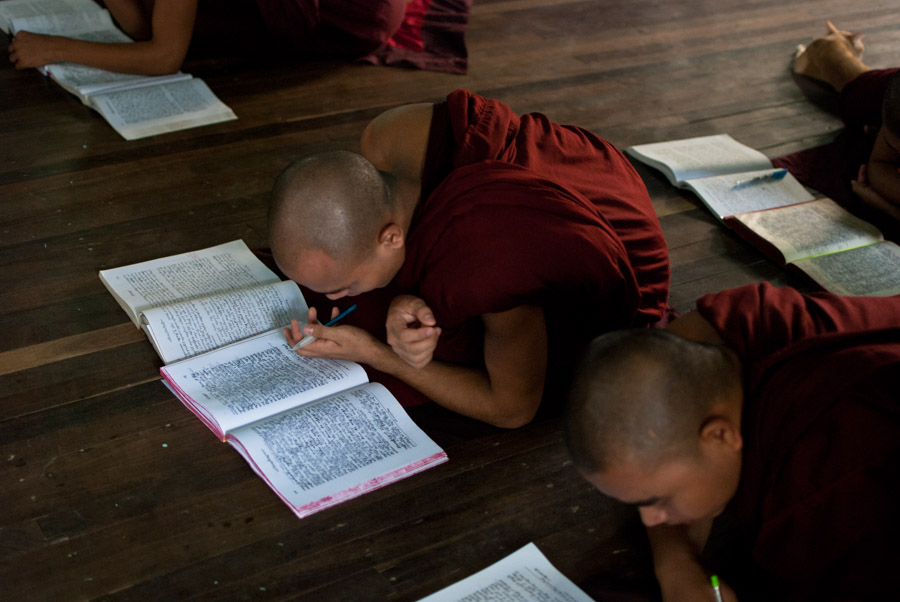

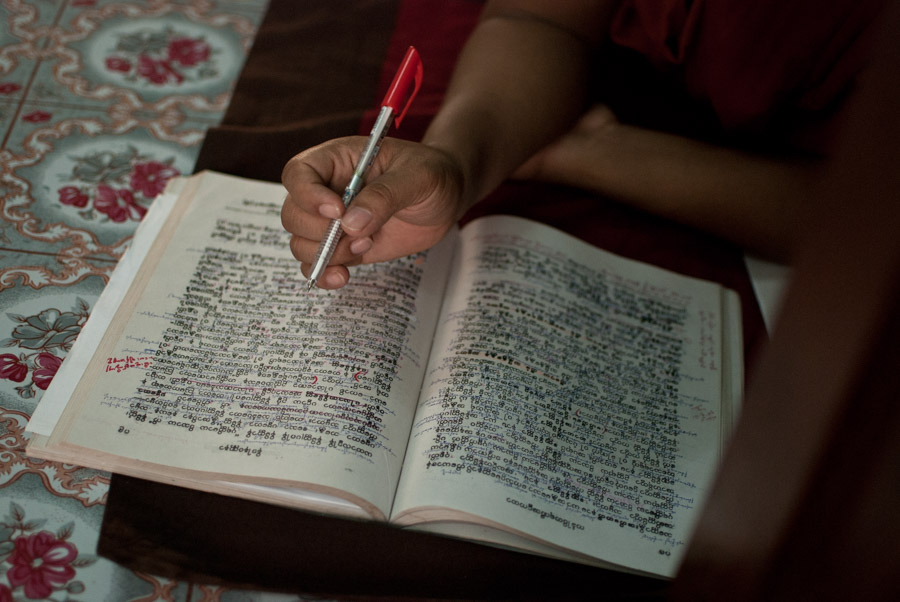

Myanmar’s most notorious monk is clearly enjoying the attention. In the hall where Ashin Wirathu presides, an entire wall is given over to newspaper clippings and large photographs of himself in various poses. One photo shows the man who has been described by some critics as the “Buddhist Bin Laden” with hands clasped beneath his chin; in another he gazes serenely at the ocean. Nearby, a painted portrait of the monk stares down over the worn floorboards where novices crouch to recite their sutras.

Wirathu is the media-savvy leader of Myanmar’s 969 movement, a hard-line nationalist group that has been accused of fueling waves of violence against the country’s Muslims and, more specifically, the Rohingya, a stateless people who live mainly in western Rakhine state. Since vicious sectarian violence erupted in 2012, tens of thousands of Rohingya are believed to have fled Myanmar, many risking — and some losing — their lives in perilous sea voyages in leaky boats. As this exodus has intensified in recent months, foreign journalists again began seeking out the man many believe is most responsible for the desperate plight of the Rohingya.

From his monastic perch, surrounded by monks and other supplicants, the 46-year-old Wirathu denied any hand in the boat crisis. “My preaching doesn’t aim to create tensions between Buddhists and Muslims,” he told Nikkei Asian Review in a weary tone. “I just give the message, like the signpost on a house that says ‘beware of dog’.”

Wirathu’s inner sanctum is at the New Masoeyein Monastery, a shaded compound in a dusty quarter of the central Myanmar city of Mandalay that sprawls along the Irrawaddy River. The atmosphere is tranquil, broken only by the chanting of novice monks and the hourly chiming of a colonial-style clock tower.

While Wirathu sports the saffron robes many Westerners associate with a life of spiritual contemplation, he peddles a poisonous message. In 2001, Wirathu founded the 969 Buddhist movement to counter what he saw as the alarming increase in the birthrate of Myanmar’s Muslim minority. (Muslims make up around 5% of the estimated 52 to 53 million population, according to official figures; Wirathu claims the real figure is more than a fifth.)

Since then, the diminutive monk has called for boycotts of Muslim-owned businesses and warned of an epidemic of Muslim rapes of Buddhist women. He has been a driving force behind a proposed package of laws to “defend race and religion.” In front of his quarters is a gruesome display, a billboard covered with alleged massacres and beheadings and desecrations — the supposed crimes of global Islam.

As for the Rohingya — frequently described, including by the United Nations, as “one of the most persecuted minorities in the world” — Wirathu and other nationalists deny they are even a proper ethnicity, instead calling them Bengalis and koewin — “sneak-ins” from across the border in Bangladesh. “If these people regard themselves as refugees I have sympathy and I want to show compassion and I’m ready to provide humanitarian assistance, but they need to be honest,” he said. “They say they come from Myanmar, and they say they are Rohingya. But actually they are Bengali.”

“My preaching doesn’t aim to create tensions between Buddhists and Muslims… I just give the message, like the signpost on a house that says ‘beware of dog’.”

Human rights activists claim Wirathu’s sermons were instrumental in priming the violence that erupted in Rakhine state in mid-2012, and its subsequent spread to Myanmar’s Burman heartland, where anti-Muslim pogroms and clashes spread rapidly throughout 2013. “Wirathu’s claim that he has not advocated or encouraged violence is utterly disingenuous,” said Penny Green, director of the International State Crime Initiative and professor of law and globalization at Queen Mary University of London. “He and ultra-nationalist monks throughout Burma [Myanmar] have been critical in fomenting Rakhine anti-Muslim violence through their concerted campaigns to stigmatize, marginalize and intimidate the Rohingya, and Muslims more generally.”

Wirathu’s hateful mantra was nurtured over many years in the monkhood. He was born in 1968 in Kyaukse, a town in Myanmar’s dusty central plain, and adopted his saffron robes after finishing the ninth grade. In 2003, two years after he founded 969, Wirathu was imprisoned for inciting religious violence and remained in jail until the government of President Thein Sein took office in 2011, initiating sweeping political and economic reforms.

Myanmar’s reforms have since been a boon for Wirathu. In 2012 he was released from prison as part of a general amnesty for political prisoners, and has been allowed to travel widely around the country preaching and cultivating his mini-personality cult. He has also capitalized on the country’s sudden growth in Internet access, communicating with his followers over Facebook — he currently has more than 62,000 followers — and through an official Android app, which relates a round-the-clock stream of Wirathu-related news and agitation.

Wirathu and other nationalist figures now loom as key players in the landmark national elections expected to take place in November. While the monk has ruled out supporting any particular political party, he said he would back candidates pledging to “defend nationalism.”

Those running for office can hardly afford to ignore the increasing clout of Myanmar’s hard-line groups. On June 2, Htin Lin Oo, a former senior member and information officer for the opposition National League for Democracy, was sentenced to two years hard labor in Sagaing, a region in the country’s central-west, after being found guilty of offending “religious feelings.” His crime? To argue, during a talk at a literary event in October, that discrimination on racial and religious grounds was incompatible with the central tenets of Buddhism.

His conviction came several months after a New Zealand bar owner and two local business partners in Yangon were jailed for three years for “insulting religion” after distributing a promotional flyer for the bar depicting an image of the Buddha wearing headphones. At both trials, members of the Association for the Protection of Race and Religion, often known as Ma Ba Tha, another group closely associated with Wirathu, protested outside the courtroom.

At the same time, many activists point out that the government has done suspiciously little to curb anti-Muslim hate speech and violence. While police cracked down on recent student protests, arresting several dozen demonstrators, hard-line nationalist groups were free to march through the commercial capital Yangon in May describing Rohingya refugees as “terrorists” and “beasts.” “Wirathu speaks freely and can go anywhere. Why don’t they do anything?” asked Ah Mar Ni, a former student activist and member of the Mandalay Peacekeeping Committee, an interfaith group formed after sectarian riots there last year.

The lack of action has led some to suspect that the nationalist resurgence has been fanned by “hidden hands” in Myanmar’s military or its proxy, the ruling Union Solidarity and Development Party. One figure often accused of backing Wirathu and 969 is Aung Thaung, a parliamentary member of the ruling USDP and a former junta minister of industry who in October was placed on the U.S. Treasury Department’s sanctions blacklist for “intentionally undermining” Myanmar’s political reforms.

“Wirathu’s claim that he has not advocated or encouraged violence is utterly disingenuous.”

While the connections have not been conclusively proven — Washington has not revealed what specific evidence led it to place Aung Thaung on the sanctions list — it is clear that the USDP stands to draw electoral dividends from the rise in sectarian tensions. The issue has already wrong-footed their main rival, Aung San Suu Kyi, Myanmar’s one-time democracy icon and leader of the NLD.

As the situation in Rakhine state deteriorated, the Nobel laureate disappointed human rights activists by remaining mostly silent, fearful of alienating her support base. “For her and the NLD to win the election is really important, and with a majority,” said Harry Myo Lin, executive director of The Seagull, a Mandalay-based human rights organization. “If she speaks out, she will face big disappointment from the majority [of] Buddhists.”

Either way, many radical nationalists seem ready to accuse “the Lady,” as she is known, of being pro-Muslim, regardless of what she says. Wirathu once worshipped Suu Kyi and even sports a tattoo of the NLD’s peacock insignia on his left arm. But in 2012 he withdrew his support, accusing her, as did human rights activists, of staying silent — in this case about the violence supposedly committed by Muslims against Buddhist Rakhines. “She has emphasized democracy, but not nationalism,” he said.

While denying that 969 receives any backing from the USDP or politicians like Aung Thaung, Wirathu said he sees President Thein Sein as a good nationalist. “I fully trust in U Thein Sein,” he said.

Politicking around ethnic issues has been a common feature of Myanmar’s troubled modern history. Robert H. Taylor, a Myanmar specialist and fellow at the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies in Singapore, has described ethnicity as “a political cocktail from which demagogues drink and politicians, rather than providing the public guidance and leadership, do little to drain off except by appeasement.” Unless somebody steps up to challenge the prevailing narrative, Wirathu and his friends will all be drinking heartily from that particular glass come November.

Published by Nikkei Asian Review, June 11, 2015.