PHNOM PENH – Ieng Sary, a veteran member of Cambodia’s communist Khmer Rouge movement and one of the few of its leaders to be put on trial for crimes committed during the regime’s 1975-79 rule, died on Thursday morning at the age of 87. He was being tried at the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), a United Nations-backed tribunal, along with two other senior Khmer Rouge leaders. The ECCC confirmed Ieng Sary’s death in a statement on Thursday morning. The cause of death was not immediately known, but he had suffered from high blood pressure and heart problems in the past and was admitted to a Phnom Penh hospital on March 4.

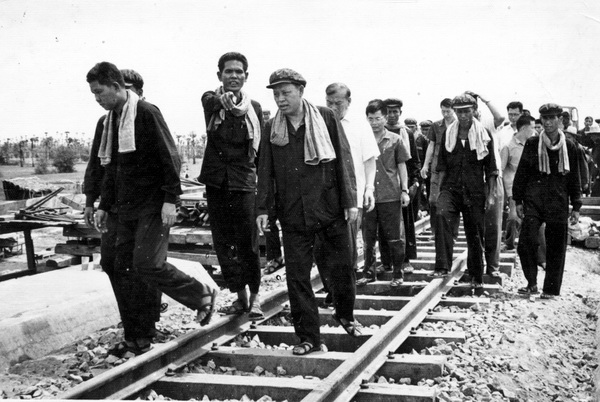

Ieng Sary’s death came before any verdict was handed down in his case, allowing him to evade responsibility for crimes allegedly committed during the Khmer Rouge’s bloody years in power. Ieng Sary was a key member of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK), alongside his brother-in-law and Khmer Rouge leader Pol Pot, before the party marched into Phnom Penh on April 1975. After their seizure of power, the Khmer Rouge treated Cambodia’s people as an expendable raw material with which they planned to forge a rural utopia of unsurpassed purity, an agrarian dream-state whose name would “be written in golden letters in world history”. Money was abolished, the cities were emptied, and the entire population was put to work on vast rural communes. Prior to the overthrow of the Khmer Rouge by a Vietnam-led resistance force in January 1979, the regime’s policies led to the deaths of an estimated 1.7 million people from starvation, execution and overwork.

Ieng Sary was born Kim Trang on October 24, 1925, in southern Vietnam. In the early 1950s, he was among a small group of Cambodian students who received government scholarships to study in France. It was there he first became immersed in communist ideas and met a young student named Saloth Sar, later to take the infamous nom de guerre Pol Pot. The pair cemented their friendship when they met and married the sisters Khieu Thirith and Khieu Ponnary. After their return to Cambodia the four went on to form the inner circle of the nascent Cambodian communist movement.

Ieng Sary returned to Cambodia in 1957, and became a member of the communist party’s Central Committee in 1960. Like many other Cambodian communists of the time, Ieng Sary taught at a high school in Phnom Penh while taking part in clandestine activities against the regime of Prince Norodom Sihanouk, who had spearheaded Cambodia’s struggle for independence from France and faced rising opposition from a small number or communists whom he famously dubbed the “Khmers Rouges” (Red Khmers). During an intensifying anti-communist crackdown by Sihanouk’s security forces in 1963, Ieng Sary, along with his brother-in-law Pol Pot, left Phnom Penh for the remote jungles of northeastern Cambodia.

The Khmer Rouge eventually came to power in a bloody civil war against the US-backed regime of General Lon Nol, who overthrew Sihanouk in 1970. From 1975 until its overthrow in early 1979, Ieng Sary was a permanent member of the CPK’s Standing Committee – the nerve-center of the Khmer Rouge regime – and served also as foreign minister. In that capacity he maintained close ties with leaders in China, the main foreign patron of the Khmer Rouge. He was particularly close to the infamous Gang of Four, the radical Chinese faction that had risen to prominence during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s. When Ieng Sary was informed of the arrest of the Gang of Four in October 1976, according to author and journalist Nayan Chanda, he was shocked, muttering, “No it can’t be true! They are good people.”

Though he later protested his innocence, experts believe Ieng Sary was closely involved in ordering the torture and mass execution of suspected internal enemies. Shortly after the regime took power, Ieng Sary made public calls for overseas Cambodian intellectuals to return and help rebuild their country; when they returned, they were arrested and placed in brutal prisons where many later died. Youk Chhang, the director of the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) which researches Khmer Rouge crimes, said there was plenty of evidence attested to Ieng Sary’s close involvement in or knowledge about purges and killings during 1975-79. “There are many documents that show he was responsible or aware, was directly or indirectly involved in instances where victims disappeared or were executed,” he said.

China comrade

After the regime’s overthrow in January 1979, Ieng Sary retained close links with China. When a barefooted Ieng Sary crossed into Thailand four days after the fall of Phnom Penh to Vietnam-backed forces, officials from the Chinese Embassy in Bangkok were there to greet him with fresh clothes and shoes to replace the sandals he had lost in the confused retreat from the capital. He was then placed aboard a Thai military helicopter to Bangkok and flown to Beijing. Throughout the 1980s, China continued to back the ousted Khmer Rouge in a civil war with the new Vietnam-installed regime in Phnom Penh.

In August 1979, eight months after the overthrow of the Khmer Rouge, a people’s revolutionary tribunal orchestrated by the new government found Ieng Sary and Pol Pot guilty of genocide and sentenced them to death in absentia. Ensconced in the jungles of western Cambodia, Ieng Sary continued on as foreign minister of the ousted regime until 1982, when he transferred the duties to his colleague Khieu Samphan, the CPK’s former head of state. Afterwards he held no formal position in the movement but remained in control of Khmer Rouge finances. Ieng Sary later became the baron of Pailin, a dusty boom-town set in gem-rich hills along the Thai border, and amassed a great personal fortune.

“The UN and the Cambodian government made a promise to punish the perpetrators of genocide. The victims deserve closure. The victims deserve to see the process completed.”

By the time the Paris Peace Accords were signed in 1991, however, his influence in the movement had begun to wane. The prominence he had enjoyed during the 1980s due to his close relationship with Beijing evaporated after the cut-off in Chinese aid in 1991. His advocacy of cooperation with the UN mission that arrived to implement the Paris Accords in 1992-93, coupled with the decidedly un-revolutionary extent of his wealth, also soured his relationship with Pol Pot, who attempted to bring his fief under closer control.

In August 1996, Ieng Sary defected to the government, bringing with him thousands of Khmer Rouge troops that hastened the end of the movement. Khmer Rouge radio denounced him as a “traitor”, accusing him of embezzling millions in Khmer Rouge funds and collaborating with the “Vietnamese aggressors, annexationists, and race-exterminators”. Ieng Sary’s defection delivered to the government two Khmer Rouge base areas – Pailin and Malai – that years of government offensives had failed to secure.

As an reward for his defection, Ieng Sary was given a royal amnesty that overturned the death penalty handed down by the 1979 tribunal. Ieng Sary thereafter lived a comfortable life, dividing his time between a shady villa in central Phnom Penh and a home in Pailin, where he still commanded great influence among the local population. His son Ieng Vuth currently serves as deputy governor of Pailin.

Though Ieng Sary long claimed his innocence, arguing after his defection that Pol Pot “was the sole and supreme architect of the party’s line, strategy and tactics”, justice eventually caught up with him. On November 12, 2007, Ieng Sary and his wife Ieng Thirith, the former Khmer Rouge Minister for Social Affairs, were arrested and put on trial at the ECCC. Ieng Sary was charged with genocide – the second time he had faced the charge – crimes against humanity, and grave breaches of the 1949 Geneva Conventions. His trial, alongside Nuon Chea, Khieu Samphan, and his wife, began in 2011 but has since been threatened by pay disputes and the advanced age of the defendants. Late last year, Ieng Thirith was ruled unfit to stand trial because she suffering from a degenerative mental illness and was released.

Ieng Sary’s death is a setback for the ECCC, whose two remaining defendants are in poor health and which has recently been plagued by a shortage of funds and allegations of political interference. Despite the challenges facing it, Youk Chhang of DC-Cam said the tribunal, and the international community that has supported it, had no option but to keep pursuing justice. “The court must move on,” he said. “The UN and the Cambodian government made a promise to punish the perpetrators of genocide. The victims deserve closure. The victims deserve to see the process completed.”

Published by Asia Times Online, March 14, 2013