Hun Sen aims at balancing US, Vietnamese and Chinese interests for Cambodia’s benefit

PHNOM PENH: As delegates touched down in Cambodia’s capital for the 20th Summit of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, they arrived in a city preened for the arrival of another, more important visitor. Chinese President Hu Jintao had just wrapped up a state visit, and Phnom Penh’s main thoroughfares were still strung with hundreds of miniature Chinese flags in celebration of the trip. The president and his wife gazed down from billboards erected at major intersections across town.

PHNOM PENH: As delegates touched down in Cambodia’s capital for the 20th Summit of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, they arrived in a city preened for the arrival of another, more important visitor. Chinese President Hu Jintao had just wrapped up a state visit, and Phnom Penh’s main thoroughfares were still strung with hundreds of miniature Chinese flags in celebration of the trip. The president and his wife gazed down from billboards erected at major intersections across town.

Cambodia is chairing the 10-member bloc in 2012, and the timing of Hu’s four-day state visit in April was more than coincidence. Looming over the summit was the ongoing dispute over the South China Sea, a potentially energy-rich area subject to competing claims by China and ASEAN member states including Vietnam and the Philippines.

Some observers suggested that Hu had come to exert pressure on Cambodia. Carlyle Thayer, analyst with the Australian Defence Force Academy in Sydney, wrote in a briefing that Hu’s visit was “designed to put pressure on Cambodia as ASEAN chair to take China’s concerns into account” and discourage formal discussion of the issue. Though it was later raised during summit talks, Phnom Penh kept the issue off the formal agenda.

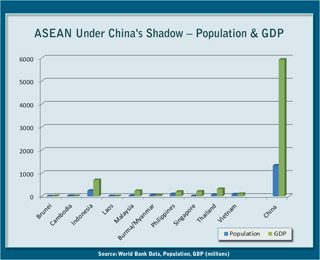

The episode demonstrated China’s rising influence in this country of 15 million. Indeed, Beijing’s global New Deal – hefty amounts of loans and investment dollars unconstrained by human rights or good governance concerns – seems almost tailor-made for Cambodia’s Prime Minister Hun Sen, a strongman autocrat who chafes at Western pressure to enact democratic reforms.

“China respects the political decisions of Cambodia,” Hun Sen announced in September 2009, as he cut the ribbon on a $128 million Chinese-funded bridge in Kandal Province. “They build bridges and roads and there are no complicated conditions.”

Chinese state banks today act like a giant petty-cash box for the Cambodian state, bankrolling construction of roads, bridges, hydropower dams, real estate developments and tourist resorts. Over the past decade, these loans and grants have run into billions, and official delegations shuttle back and forth between the two countries each year, penning sunny bilateral agreements and spouting reams of mutual praise.

Beijing’s global New Deal, hefty loans unconstrained by human rights concerns, is almost tailor-made for Cambodia.

Bilateral trade between the two countries has also boomed. Thailand and the United States remain Cambodia’s top trade partners, but China is well on the way to eclipsing both in the next decade. Two-way trade topped $2.5 billion in 2011, driven mostly by imports of Chinese machinery, cars, food, electronics, furniture and medicines, and the two countries have ambitiously pledged to double this amount to $5 billion by 2017. Shortly after his arrival, Hu hailed the “good-neighborly ties of friendship” between the two countries, which have “withstood the test of time… and moved forward steadily.”

Relations were not always so rosy. China was the main foreign patron of the communist Khmer Rouge, whose project of utopian social engineering led to the deaths of an estimated 1.7 million people between 1975 and 1979. Even after the regime was overthrown, Beijing continued to funnel millions in cash and materiel to Khmer Rouge insurgents waging a civil war against the new Vietnam-backed regime in Phnom Penh. This funding was eventually cut off in 1990, but Beijing’s support for the Khmer Rouge cast a long shadow; in 1988, Hun Sen described China as “the root of everything that was evil” in Cambodia.

But new interests soon came into alignment. After Hun Sen ousted his domestic rivals in a bloody factional coup d’état in July 1997, prompting outrage in the West, China immediately recognized the status quo and offered military aid. Then, in 2000, Chinese President Jiang Zemin arrived in Cambodia for an official visit, the first by a Chinese leader since 1963. In the years since, bilateral assistance – mostly in the form of soft loans – has come thick and fast.

Under China’s influence, the balance of power in Cambodia has slowly shifted. Chinese largesse has undeniably acted as an escape hatch for Hun Sen: Constrained for many years by his reliance on Western donor money, he now has a freer hand to evade Western countries’ calls for democratic reforms. “Aid from China has worsened the governance problem,” said Ian Storey, senior fellow at Singapore’s Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. “The Cambodians can say, ‘if you attach strings to this aid, then we’ll simply go with the Chinese.’ So that worsens the situation, the corruption problem [and] the absence of the rule of law.”

“Cambodia cannot be bought,” Hun Sen insists. Despite such protests, though, China’s cash is bound with invisible strings.

Critics express concern about the environmental effects and lack of transparency surrounding many Chinese-backed infrastructure projects, including the controversial Boeung Kak lake development in central Phnom Penh, which rights groups claim has led to the illegal eviction of around 4,000 families, and the massive gambling and tourist resort development under construction in Botum Sakor National Park in the country’s southwest. Compounding these concerns are reports of mistreatment of Cambodian workers on Chinese construction sites.

“China has become more and more arrogant in Cambodia now,” said Lao Mong Hay, a political analyst based in Phnom Penh. “They behave more and more like the colonialists of the past.”

For its own part, the Cambodian government denies it’s subject to undue Chinese influence. “What I hate and am fed-up with is talk about Cambodia working for China,” Hun Sen told reporters at a fiery press conference at the end of the ASEAN Summit. “Cambodia cannot be bought.”

Despite such protests, though, China’s cash is bound with invisible strings. This was dramatically demonstrated in December 2009, when the Cambodian government forcibly deported 20 ethnic Uighur asylum seekers to China. The timing of the deportation – a day before the arrival of a Chinese official carrying a $1.2 billion package of grants and loan agreements – left few in doubt that extreme pressure was brought to bear on Phnom Penh. The following March, when the United States retaliated for the move by suspending a planned shipment of military trucks, Beijing simply filled the breach with its own shipment. Cambodia has also thrown its support behind the One-China policy: In August 2010, Hun Sen warned provincial governors not to permit the establishment of Taiwanese government bureaus or offices in their provinces – or risk immediate dismissal. “Cambodia’s painted itself into the Chinese corner,” said Lao Mong Hay. “It has been lured by the Chinese Yuan.”

Despite such protests, though, China’s cash is bound with invisible strings. This was dramatically demonstrated in December 2009, when the Cambodian government forcibly deported 20 ethnic Uighur asylum seekers to China. The timing of the deportation – a day before the arrival of a Chinese official carrying a $1.2 billion package of grants and loan agreements – left few in doubt that extreme pressure was brought to bear on Phnom Penh. The following March, when the United States retaliated for the move by suspending a planned shipment of military trucks, Beijing simply filled the breach with its own shipment. Cambodia has also thrown its support behind the One-China policy: In August 2010, Hun Sen warned provincial governors not to permit the establishment of Taiwanese government bureaus or offices in their provinces – or risk immediate dismissal. “Cambodia’s painted itself into the Chinese corner,” said Lao Mong Hay. “It has been lured by the Chinese Yuan.”

Whatever the benefits of Chinese patronage, others contend that Cambodia is unlikely to fall fully into Beijing’s camp. The US, for instance, remains one of Cambodia’s main trading partners and a key export market for its growing garment sector. Relations with Washington have also improved since the early 2000s, especially in military-to-military terms. US assistance to Cambodia, suspended after the 1997 coup, was restored in 2007, and two countries now host annual military exercises focusing on counterterrorism and international peacekeeping operations. Though offset somewhat by China’s rising influence, Cambodia also remains close to Vietnam – a newly-minted US ally and political patron that put Hun Sen’s regime in power after overthrowing the Khmer Rouge in 1979.

In fact, Hun Sen’s aim is strikingly similar to the strategy employed by previous Cambodian leaders, including King Norodom Sihanouk in the 1960s. “Cambodia wants to accommodate all [countries],” said Chheang Vannarith, executive director of the Cambodian Institute of Cooperation and Peace, adding that the door “remains open” for Western donor countries.

Balancing competing outside powers to its own benefit was a risky game for the king and remains risky now, but is arguably a canny policy for a small country occupying an increasingly important role in the triangular Great Game between China, Vietnam and the US.

[Published by YaleGlobal Online, May 16, 2012]