PERHAPS THE BEST way to grasp the sad and desperate state of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea is to glance at a satellite photo of Northeast Asia by night. From this vantage point, a few hundred miles above the earth’s surface, the southern half of the Korean peninsula is fretted with dazzling lights, neon-ribbed and pulsing with energy. Over the northern border, however, the land lies under a blanket of Stygian black, a near-total absence broken only by a tiny pinprick: the showcase capital Pyongyang.

A few years ago, in her fascinating book Nothing To Envy, the American journalist Barbara Demick described how this nightly blackout dominates ordinary life in North Korea. Since the country’s economy collapsed in the early 1990s, North Koreans have learned to live without power, a fact of life that has retarded industry and development and plunged the nation into famine. Paradoxically, however, the darkness also hides the awful reality of life and allows some measure of freedom. She tells the story of one teenage girl who takes advantage of the darkness to arrange secret meetings with her sweetheart, and wanders with him on cracked pavements under the brilliant night sky. Lenin famously said that communism equalled “electrification and Soviet power.” After losing its access to electricity, North Koreans now at least have some sort of respite from the prying eyes of Lenin’s heirs.

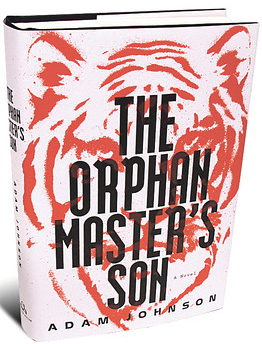

Like many of the North Koreans whose stories Demick tells, Park Jun Do, the hero of Adam Johnson’s new novel, is accustomed to the darkness. Indeed, he has been taught to flourish in it: plucked from an orphanage at the age of fourteen, Jun Do is drafted into the army and trained to fight in pitch darkness, confined to the unlit tunnels that run deep under South Korean territory. From this starting point, Johnson sweeps the young man up into a grim adventure that leads him through the various warrens of the North Korean state—from its prison camps to the Pyongyang opera—and gives us a surprisingly convincing (although slightly lengthy) fictional panorama of the world’s most isolated and repressive state.

Any novelist attempting to tackle North Korea runs considerable risks, either of being overshadowed by the bleak majesty of the topic or falling prey to tinny clichés about “the hermit kingdom.” In researching his book, Johnson made one trip to the North and spent seven years reading the testimonies of North Korean defectors, and the legwork has paid off: he has rendered his world in a surprisingly vivid manner. Every backdrop—from the looming martyrs’ monuments that dot Pyongyang to the flow and cadence of North Korean propaganda radio broadcasts—resonates with verisimilitude.

This is a world of near-total euphemism and dissimulation, where all aspects of life are dominated by the propaganda that is blared each day into every household. As a counterpoint to the literal darkness of the North Korean night, this blanketing state control also creates a sort of metaphorical fog, through which Johnson’s characters grope blindly. Each goes by a nickname or a pseudonym, their true identities and origins buried under the swaddling of their official—and ever-shifting—“biographies.” In the torture cells of Division 42, where these identities are broken down and reconstructed, a nameless interrogator describes the pain of torture as “a dance with identity”—a pas de deux with only one possible outcome. In the following passage, he speaks about the torture of a university professor caught playing illegal South Korean pop songs to his students.

We ramp up the pain to inconceivable levels, a shifting, muscular river of pain. Pain of this nature creates a rift in the identity—the person who makes it to the far shore will have little resemblance to the professor who now begins the crossing. In a few weeks, he will be a contributing member of a rural farm collective, and perhaps we can even find a widow to comfort him. There’s no way around it: to get a new life, you’ve got to trade in your old one.

“For us, the story is more important than the person,” another character, later to be purged, describes it: “If a man and his story are in conflict, it is the man who must change.” (As if to underline this rift, sections of Johnson’s narrative are written in the style of propaganda broadcasts, which provide an increasingly absurd—almost magical realist—parallel to the main action. The book both opens and closes with these hectoring passages.)

Park Jun Do, Johnson’s main protagonist, is one of many characters who occupy both sides of this equation, and the one who bears most of the strain of the conflict. Conscripted into a work camp for orphans after his mother (a singer) is kidnapped and dispatched to entertain the Pyongyang elites, Jun Do—he is named after one of North Korea’s revolutionary heroes—soon becomes an agent of the state’s security apparatus, traveling abroad to kidnap foreigners and monitor foreign radio broadcasts. After failing in his main mission as part of an official delegation to Texas (where his name is tellingly mistaken for “John Doe”), Jun Do is pitched into the deepest recesses of the North Korean prison system. This is a place of horror, where doctors drain the blood from dying prisoners in order to keep the hospitals of Pyongyang well-stocked, and lobotomies are performed on inmates with a long nail—the “preferred method of reforming corrupted citizens.” One hopes—probably in vain—that these are figments of Johnson’s imagination.

After taking the identity of another man, Jun Do manages to escape the camp and unexpectedly falls in love with one of the North Korea’s most famous actresses. As Jun Do rises through the ranks, using a new identity and moving into the world of the Pyongyang elite, he also edges closer to the penumbra of danger surrounding the “Dear Leader,” Kim Jong-Il himself.

The “Dear Leader” that appears in these pages is ingenious: a trickster, impish and insecure, whose good humor is almost more dangerous and unpredictable than anything else. In this respect, Johnson’s Kim bears a certain family resemblance to the Stalin conjured up in The Case of Comrade Tulayev, Victor Serge’s great novel of the Soviet purges. This is the sort of avuncular despot who would beam and clap you on the shoulder one moment, and then ship you off to the Gulag the next. Or as one of Johnson’s characters says of Kim fils, “I didn’t know which was worse, to displease him or to please him.”

Johnson has said he actually had to rein in his own version of Kim Jong-Il, worried that the real-life excesses of the Dear Leader would come across as phoney or contrived. But it is this atmosphere of caprice and playful menace, rather than the platform shoes and Swedish concubines, that make Johnson’s Kim chillingly effective. Backed by the world of make-believe created by official propaganda, this is a leader who treats North Korea and its people as personal playthings, to be used and disposed of at will. (One cannot help being reminded here of the Führer himself, stooped and gazing with malign enthusiasm over his prized architectural models.)

When Kim Jong-Il died last year, many observers in the West were puzzled by the displays of public mourning that took place in Pyongyang. For days, apparently ordinary men and women wept and flagellated themselves in the snow-filled squares of the capital, like aggrieved relatives ready to heave themselves into the grave of a departed loved one. Surely these tears had to be fake, coerced by peer pressure, like the crowd of Soviet officials afraid to be the first to stop applauding. Surely these people could not possibly accept the absurd lies about this withered tyrant, whose death, according to North Korean state media, caused frozen lakes to crack and the hallowed Mount Paektu to glow red.

Much of the mourning was undoubtedly exaggerated, but few stopped to consider that the show of affection may also have also been partly genuine. One young North Korean woman I met in Seoul said she once viewed Kim Jong-Il and his father Kim Il-Sung “as gods”; it was only when she got out to the south that she saw the awful extent of the lies about the Dear Leader and the desperate situation in her homeland.

In The Orphan Master’s Son, Johnson has provided a striking sketch of this horrific psychological landscape; he shows that the people of North Korea are victims of a sort of national Stockholm syndrome, by which affection for the trinity of Kims is coerced, yet also strangely heartfelt. To love one’s oppressor: many nations and political systems have attracted the epithet “Orwellian,” but Johnson’s novel is a timely reminder that none have deserved it to such a chilling extent.

[Published by The New Republic, April 16, 2012]