Reading North Korea’s comic book propaganda.

THIS spring, the comic book world awoke to the earth-shaking news that Superman—the quintessential American superhero—was no longer a U.S. citizen. The revelation came in Action Comics No. 900, published in April, in which the superhero renounced his citizenship after getting the U.S. government into hot water by participating in an Iranian street protest. “I’m tired of having my actions construed as instruments of U.S. policy,” Superman says with gravitas. “‘Truth, justice, and the American way’—it’s not enough anymore.”

Superman’s shift away from his adoptive country suggests that being a crusader for global justice is no longer the simple occupation it once was. There are no such qualms for Gen. Mighty Wing, who is the star of comic books in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. The North Korean regime’s comics, known locally as gruim-chaek (“picture books”), are mass produced on thin, low-quality paper and distributed widely among the isolated regime’s privileged classes. As you might expect, they are unabashedly propagandistic, serving up outlandish plots that help inculcate reverence for Great Leader Kim Il Sung and the regime’s perennial battles against imperialists of all stripes.

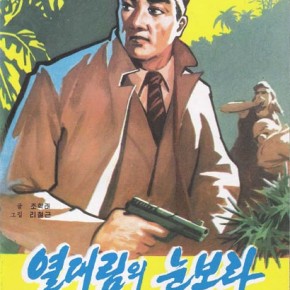

- ‘Blizzard In The Jungle’ (2001)

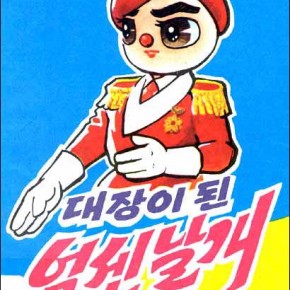

- ‘Great General Mighty Wing’ (1994)

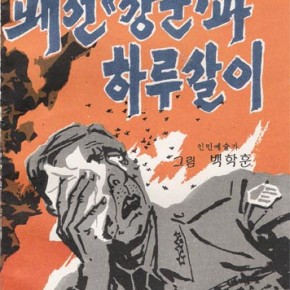

- ‘General Loser and the Gnats’ (2005)

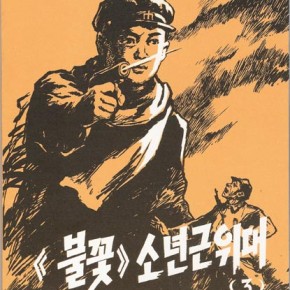

- ‘The Fireflower Youth Guard’ (1999)

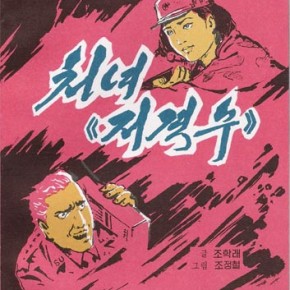

- ‘Sniper Maiden’ (2004)

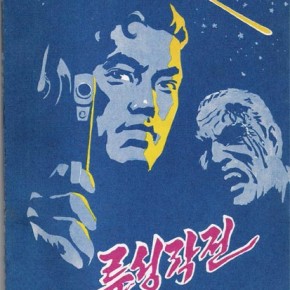

- ‘Operation Shooting Star’

In Great General Mighty Wing (1994), a sort of Kimilsungist Disney fable, the honeybee general Mighty Wing leads his hive in a successful attack on an alliance of wasps and spiders that are plotting to seize control of the hive’s Garden of 1,000 Flowers. Mighty Wing also discovers a way to irrigate the garden and drive up honey production, all while fighting against traitorous internal elements and the wasps’ secret air-borne “missile”—a bow and arrow. Mirroring the action, the margin of each page bears a revolutionary aphorism, ranging from the homely (“Happiness seeks out the home where laughter blooms”) to the paranoid (“Never think of the enemy as a lamb—always consider him a jackal”). The more militant the sayings get, the less comfortably they sit alongside the brightly colored, child-friendly insect characters.

Blizzard in the Jungle (2001) is set in an unnamed African country, where a plane carrying North Korean agents is brought down in the jungle by gangsters eager to get their hands on a briefcase full of “secret documents.” Using the wisdom of Kim Il Sung’s revolutionary juche ideology, and enriched by the power of Korean-grown ginseng, hero Kim Yeong-hwan leads survivors to safety. The North Koreans are depicted as natural leaders (“You are followers of the juche philosophy, so I can put my trust in you,” one of the natives gushes), and two Americans who break off from the collective in typical individualistic fashion are devoured by crocodiles. “I saw this in a movie once,” one says as they tread off down their river to their doom.

Heinz Insu Fenkl, a professor at the State University of New York at New Paltz who has translated a number of North Korean comics, says they are interesting for the insights they offer into the “psychological infrastructure” of North Koreans: the daily diet of propaganda that conditions even well-educated citizens to love and revere their leaders. Many of the comics also represent a revival of Korean folk culture and history, including retellings of famous episodes from Korea’s dynastic history and the Communists’ heroic struggle against Japanese imperialism. “What the North Koreans are doing in comics is parallel to what South Korea and China are doing in film, which is going back and re-imagining their history,” he says.

They also grapple with contemporary realities. The plot of Mighty Wing refers to the desperate drought and famine that ravaged the country around the time the book was published. “The ironic effect is that [the comics] made me much more sympathetic to the condition of ordinary North Koreans,” Fenkl says. “The comic books are reflecting things that are contemporary social reality.”

Like all North Korean artwork, comics are produced according to revolutionary principles developed in the 1960s and 1970s by Dear Leader Kim Jong-il, and many of the writers and artists are drawn from the prestigious Kim Il Sung Academy in Pyongyang. “All the production is controlled by the state. Even things that are just categorized as entertainment have to go through the state filter,” says Fenkl, who has collected a range of comics during trips to China and from colleagues who have visited North Korea. The principles of composition, similar to the Socialist Realism of the Stalinist era, dictate form as well as content. “The style tends to be fairly representational. … You don’t find high fantasy elements,” says Fenkl.

There’s also a notable dearth of humor. Fenkl, who has read more than 200 of the comics, says he has never seen one that would qualify as “light comedy.” Andrew Holloway, in his memoir A Year in Pyongyang, made a similar observation about North Korean television in the 1980s: “One thing you do not get is comedy,” he notes drily. “Cultivation of the comic outlook on life could have a very damaging effect on people’s attitude toward the Juche Idea.”

Despite their low production quality, Fenkl says the aesthetic is well-developed, similar to the comic books he remembers reading as a child in South Korea in the 1960s. Others have a surprising level of conceptual complexity. The Secret of Frequency A (1994) tells the story of a North Korean “elite science youth squad” that teams up to help an African nation rid itself of a mysterious plague of locusts. The cause of the plague? A coterie of nefarious American agents—including a Nazi war criminal and a buck-toothed Japanese acoustical engineer—have utilised a particular frequency of the note A to advance imperialist interests in Africa.

The African setting, a feature of many of the books, reflects the fact that North Korea once had—and in some cases still maintains—strong relations with many African nations. Intriguingly, the conspiracy in Frequency also cribs from a fringe theory, advanced in this article by Leonard G. Horowitz, claiming that the standard 440Hz A tuning introduced before World War II was an “imposed frequency” that created “greater aggression, psychosocial agitation, and emotional distress” among the population. Fenkl says that it’s surprising how much research appears to have gone into the comic’s Tintin-esque plot.

North Korea even maintains a sideline in crude political satire, such as General Loser and the Gnats (2005), a collection of episodes poking fun at U.S. President George W. Bush. In one section described by Fenkl, Bush asks members of his Cabinet about his popularity. He is informed that people named Bush are changing their names to express displeasure at his presidency. The president is also shocked to learn that a number of soldiers who took his name to honor his leadership only did so after being bribed. (It will come as no surprise that the “American Empire” came in dead last on North Korea’s most recent global happiness index.)

But despite the heavy-handed North-Korea-as-global-savior theme, the comics do seem to be genuinely popular. “Certainly when I’ve bought them, my interpreter, driver, and everyone else likes to borrow and read them,” says Glyn Ford, author of North Korea on the Brink: Struggle for Survival. Some are even pretty entertaining. “They are comics, not the Works of Kim Il Sung, after all.”

[Published in Slate magazine, June 21, 2011]