ONE of Cambodia’s oldest known languages is teetering on the brink of extinction, according to language experts, who say its loss will erase the last vestiges of a culture stretching back far into Southeast Asia’s prehistory. The S’aoch tongue, a distant relation to modern Khmer, is now spoken by just a handful of villagers in Kampot province and linguists say it is unlikely to survive beyond the current generation.

Jean-Michel Filippi, a professor of linguistics at the Royal University of Phnom Penh said the S’aoch, confined to the small hamlet of Samrong Loeu, now number just 110 people, of whom barely a tenth speak the language. “There are no more than 10 fluent speakers [of S’aoch],” said Filippi, who has transcribed around 3,500 S’aoch words in the course of his study of the language. Even these could only be considered “virtual” speakers, he said, in the sense that day-to-day life no longer gave them any real opportunities to use their mother tongue.

Based on interviews with the S’aoch, Filippi said the banning of the language by the Khmer Rouge and the group’s increasing contact with the Khmer majority had sped up the “rejection” of its native norms and practices. He cited one S’aoch villager as saying that the mother tongue had died out because it no longer had much practical relevance for the community: “The people who have money use the Khmer language. Sometimes we may use it, but strictly between ourselves. And when there are Khmer people we only use Khmer.”

S’aoch belongs to the Austroasiatic family of languages, an indigenous language group that also includes Khmer and Vietnamese, as well as minority languages in India, Myanmar and Malaysia. Gerard Diffloth, a historical linguist and retired professor of Austroasiatic languages, said the word s’aoch – a modern Khmer term meaning “skin infection” – hinted at the group’s historically unequal relationship with the Cambodian majority, but belied the tongue’s scientific and cultural importance.

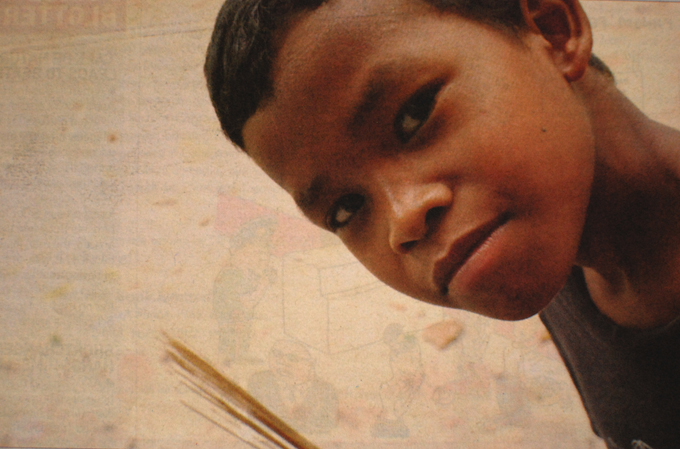

An ethnic S'aoch child from Kampong Loeu village in Kampot province. (Photo: Jean Loncle)

“It’s very ancient, much more ancient than Angkor and pre-Angkor. It’s so ancient that even [researchers] don’t really know how far back it goes,” he said, adding that its inevitable loss will destroy one of the few remaining links with the ancient history of mainland Southeast Asia. “When they disappear, a whole chapter of history will just vanish,” he said.

Despite the decline in the language’s use, S’aoch, on the rare occasions it is used, has remained relatively immune to the linguistic influence of Khmer and remains a time capsule from the depths of prehistory. “The knowledge the elder members of the community have of their language remains intact, a kind of virtual or frozen knowledge,” Filippi said.

Linguistically, S’aoch has “almost unique phonetic peculiarities”, he added, including a “breathy” voice – which adds a “sepulchral” effect to the speaker’s tone – and a “creaky” voice, resulting from the insertion of a glottal stop in the middle of a syllable.

Ros Chantrabot, deputy director of Royal Academy of Cambodia, said studies of the S’aoch and the Kingdom’s other “micro-languages” were thin on the ground and voiced concerns they would eventually be lost. “I am concerned about [losing] the Poa, So’ong and S’aoch languages,” he said. “We have to research them in depth in order to preserve and understand our history clearly.”

But experts said the fate of the S’aoch is hardly an isolated case, and that efforts to revive such languages around the world rarely managed to stem the tide of cultural absorption. Revitalisation, usually pursued through the creation of a written script and teaching materials in native languages, is also unlikely for Cambodia’s smallest language groups. “It is obvious that a revitalisation would not be possible in the case of the S’aoch,’ Filippi said. “In many cases, the speakers of endangered languages consider that speaking their language and teaching it to the children is a handicap and they prefer to switch to the majority language.”

Filippi noted that two languages disappear each month and that 94 percent of those spoken worldwide are confined to less than 2 percent of the world’s population. Half of the world’s 6,700 languages, he added, will likely disappear in the next century.

Diffloth said the process of modern nation building and economic development had gradually eroded the cultural isolation enjoyed by micro-languages such as the S’aoch, exposing them to the use of standardised national languages. “[The problem] is the idea that a country should speak one language,” he said. “Unfortunately, it’s impossible to avoid.” WITH REPORTING BY SAM RITH

[Published in the Phnom Penh Post, November 13, 2009]