As the government accepts millions of Chinese aid and investment dollars, observers remain divided on whether Beijing’s meteoric rise will help or hinder the country over the long term.

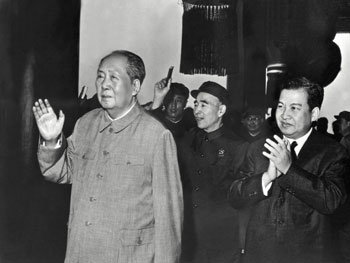

- Chinese premier Mao Tse Tung and then-Prince Norodom Sihanouk survey a mass gathering in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square following Sihanouk’s overthrow in March 1970. (Photo: AFP)

AT a September 14 ceremony marking the construction of the US$128 million Cambodia-China Prek Kdam Friendship Bridge in Kandal province, Prime Minister Hun Sen hailed the recent growth in aid and investment from China, saying it was helping to strengthen the country’s “political independence”.

“China respects the political decisions of Cambodia,” he told his audience. “They are quiet, but at the same time they build bridges and roads, and there are no complicated conditions.”

With a flourishing economy and a new-found international confidence, China is on the rise in Southeast Asia, and Cambodia – a small but important corner of Beijing’s regional backyard – has been one of the key beneficiaries. Last month, officials announced they were looking to secure $600 million in Chinese funds for infrastructure projects, including two bridges and the rehabilitation of National Road 8 linking Kratie and Mondulkiri provinces.

The announcement came on top of the $880 million in loans and grants received since 2006, including the $280 million Kamchay Dam in Kampot and the recently-completed $30 million Council of Ministers building.

Chinese embassy spokesman Qian Hai said Chinese investments in the Kingdom totaled about $4.5 billion, a success built on a policy of respecting Cambodia’s right to deal with its own affairs. “We do not interfere in the internal affairs of Cambodia,” he said, adding that Phnom Penh has reciprocated by recognising Beijing’s One-China Policy, which advocates peaceful reunification between Taiwan and the Chinese mainland. “We always respect each other’s sovereignty.”

As in countries across the developing world, China’s global sales pitch – millions of dollars in aid and investment decoupled from the issue of human rights or democratic reform – has won it many friends in Phnom Penh. Hun Sen’s remarks about Chinese “non-interference”, however, have opened up a fresh debate about the long-term effect of Chinese aid and investment to Cambodia, with observers remaining divided on whether China’s rising tide will uplift the country or scuttle its progress on human rights and reforms.

International analysts say China’s policies in Cambodia are only one aspect of its engagement with the region as a whole – a strategy based on re-establishing its traditional role as the “Middle Kingdom” in the region. Carl Thayer, a professor at the Australian Defence Force Academy in Sydney, said China’s strategy of “non-interference” had won the country increasing influence in Southeast Asia, where it is seen as a shield against pressure from the United States and other Western countries. “Chinese aid offers an escape hatch for countries under pressure from the West [that] promote human rights and democratic reform,” Thayer said.

Inevitably, the rising Chinese influence has prompted concerns that funds could wean the government off Western aid “burdened” with human-rights and good-governance conditions – rolling back democratic reforms implemented since the early 1990s. Joshua Kurlantzick, a fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations in Washington and the author of Charm Offensive: How China’s Soft Power is Transforming the World, said Chinese aid was likely to have a “corrosive” effect on good governance and human rights in Asia. “Hun Sen knows how to play China off of the Western donor group, and China’s aid – even if not necessarily linked to any downgrading of human rights – could have the effect of a kind of race to the bottom on human rights,” he said.

Sophie Richardson, Asia advocacy director at the US-based Human Rights Watch, agreed that unconditional Chinese aid to Cambodia could act as a “financial lifeline” that might otherwise be cut by Western donors. She said, however, that Western nations often failed to work together effectively to set and enforce aid conditions in Cambodia, meaning that China’s growing presence was unlikely to have any long-term effect on human rights. “The most important point – and key problem – is that the government in Phnom Penh … seems determined to be extraordinarily abusive, regardless of whoever’s money is on offer,” she said by email.

Cambodia, like many Southeast Asian countries, has had a long and stormy relationship with Beijing. Chinese leaders had a close friendship with then-Prince Norodom Sihanouk during the 1950s and 1960s, and offered Sihanouk asylum after he was overthrown by a republican coup in March 1970. China’s staunch support for the Khmer Rouge regime soured the relationship for the remainder of the Cold War, leading Hun Sen to refer to China in a 1988 essay as “the root of everything that was evil” in Cambodia. But as memories of Cambodia’s long civil war have faded, historical grievances have been replaced by more practical concerns. After Hun Sen ousted then-first Prince Norodom Ranariddh in the factional fighting of July 1997, China was the first country to recognise his rule.

Despite a recent influx of Chinese yuan, there is no indication the government is ready to turn its back on the West. Chea Vannath, an independent political analyst based in Phnom Penh, said that growing Chinese influence would likely be used to counterbalance the influence of Western countries – a vital strategy for a country of Cambodia’s size. “I think that what the government is trying to do is to diversify its aid…. It is eager to strike a balance,” she said. “As a sovereign government, Cambodia needs aid from both sources.”

Regarding the possibility that Chinese aid could erode human rights, Chea Vannath said global winds were blowing in the opposite direction, promoting pluralism and transparency through international groupings such as ASEAN and the World Trade Organisation. Cambodia is a member of both bodies. Kurlantzick also cited the increasing openness of Beijing’s aid and investments in Cambodia, saying that donors were “less in the dark” about Chinese money than previously, thus increasing the potential for future cooperation.

Thayer agreed that rumours of a drop in Western influence were exaggerated and said countries had little to gain from throwing their lot in exclusively with one side or the other. “All the countries of Southeast Asia, to varying extent, have long adjusted to China’s rise and political influence,” he said. “They do not want to be put in a position of having to choose between China and the United States.”

Thayer noted that the US is still Cambodia’s largest export market, and that President Barack Obama had encouraged trade with Cambodia as a means of recouping American prestige amid a region in which it has a troubled recent past. Ultimately, Chea Vannath said, Chinese influence – dating back to the 11th century – is a permanent reality for Cambodia but one that, in combination with contributions from the US and Europe, stands to deliver long-term benefits for the Kingdom. “Culturally and historically, on and off, good and bad, we’ll always have China with us,” she said.

[Published in the Phnom Penh Post, October 6, 2009]