Phnom Penh’s small Caodai temple, the Cambodian outpost of a curious southern Vietnamese religious sect, continues to attract local converts, attracted by its all-inclusive religious doctrine

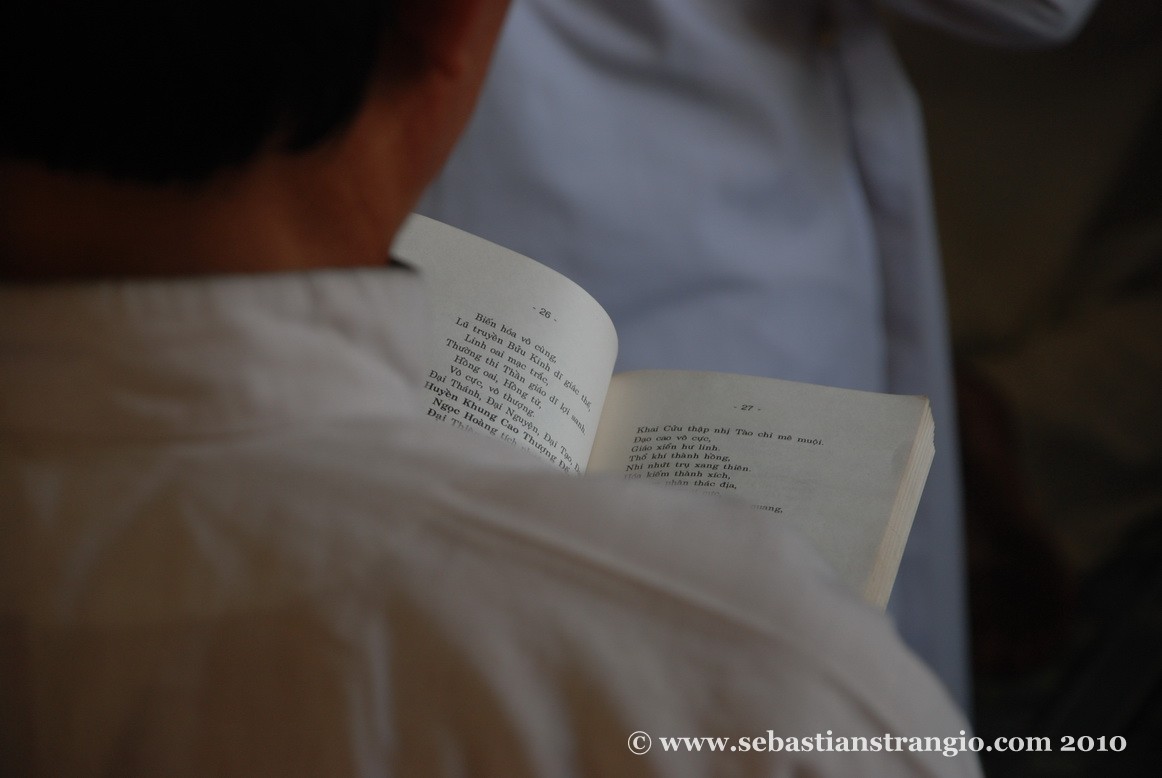

A GONG rings out over the city, swallowed by the noise of the morning traffic, as the devotees arrive in their Sunday best – flowing white robes and small black caps for the men – and gather in the main prayer hall. Incense chokes the air as three priests, clad in gold and red, lead the congregation in chants under the unblinking gaze of the Divine Eye, suspended in a sky-blue frame above the altar. For adherents of Caodaism, a religious sect native to southern Vietnam, the ceremony is a fortnightly ritual that emphasises universal peace and the oneness of man, God and the universe.

“Since I started participating in Caodaism, my family is happier because I stopped using violence against my wife, stopped drinking wine and stopped having a mistress,” says Phan Van Quang, 64, who started going to the temple when he was 25 to “understand the dharma” and gain good fortune.

Phnom Penh’s Caodai temple, a shaded citadel down an alley off Mao Tse Toung Boulevard, has been the Cambodian home of Caodaism since 1934, and temple elders say that before the Khmer Rouge, it boasted a congregation of over 10,000. Though that number has dwindled to around 2,000 today, the temple continues to find eager converts among the city’s Vietnamese community.

“Day after day, more and more people are respecting Caodai,” said Tran Van Ngoan, the head of temple security. “We do not force people to participate in this religion. People respect it by themselves voluntarily.” Today, he said, there are over 1,300 Caodai temples in southern Vietnam, and over 5 million adherents, spread as widely as Japan, North America, Europe, and Australia.

Caodaism – more properly known as Cao Dai Dam Ky Pho Do, or the “Third Great Universal Religious Amnesty” – was born in southern Vietnam in the early 1920s, when Vietnamese civil servant Ngo Van Chieu claims to have made contact with spirits who communicated to him a symbol – the “all-seeing eye” – and a new creed reconciling the great religious philosophies of East and West.

In an attempt to create the ultimate religious synthesis, Chieu poured everything but the kitchen sink into Caodaism, which counts Sun Yat-sen and French author Victor Hugo amongst its saints. Although the doctrine itself is a melange of Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism, it also incorporates arcane aspects of 19th-century French spiritism, including seances, Ouija-boards, and the bizarre practice of pneumotographie, in which pieces of paper are placed in envelopes and suspended above the altar, where they are supposedly inscribed with messages from God.

Caodai architecture is the same synthetic brew as its doctrine, combining Buddhist sculpture and European baroque into what British author Graham Greene once described as a “Walt Disney fantasia of the East”. Though a more modest affair than its elder brother, the Caodai Holy See in Vietnam’s Tay Ninh province, Phnom Penh’s temple is the same technicolour feast, with menageries of dragons, lotus flowers and coloured flags covering every available surface.

Tran Van Ngoan said that in order to participate in the religion, adherents have to adopt a vegetarian diet, starting with six days a month during the first six months, and then 10 days a month thereafter. But attendance at the temple is only required for the main fortnightly services, and the religion – unlike Christianity or Islam – does not demand strict loyalty from its adherents. “I follow both the Caodai and Buddhist religions – they are not so different from each other,” says Yin Chhay, a 56-year-old Khmer from the city’s Meanchey district, who attends four Caodai services a month but goes to the pagoda for Buddhist festivals.

Phnom Penh’s Caodai temple also has a peculiar claim to fame as the resting place, from 1959 to 2006, of Pham Cong Tac, one of the religion’s founders and first known “mediums”. Known to adherents as the Ho Phap, or “Defender of the Faith”, Tac also brought Caodaism to Cambodia in 1927, when he was posted to Phnom Penh as a junior official in the French colonial administration.

Hum Dac Bui, a spokesman for Caodai.org, a California-based non-profit organisation, said Tac was sent to Cambodia to prevent him spreading the religion further in Vietnam, but that he quickly went about establishing it in Phnom Penh. Upon his return to Vietnam, the religion continued to grow at a remarkable pace under Tac’s leadership. By the 1950s, an estimated one in eight South Vietnamese was a Caodai, and the religion ran most of Tay Ninh province as a feudal theocracy, collecting its own taxes and maintaining a standing militia of tens of thousands of men. Tac had achieved such stature within Vietnam that in May 1954 he attended the Geneva Conference, where he tried in vain to prevent the partition of the country.

But when South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem, a staunch Catholic, came to power in 1955, the domestic political calculus began to turn against the Caodai. In 1956, Diem forcibly disbanded the Caodai militias and other nationalist rivals. Tac and a close circle of followers sought political asylum in Cambodia, where he died in 1959. “Pham Cong Tac moved to Cambodia because he did not want to see our Vietnamese people fighting with each other. He asked for his body to be taken back only when Vietnam was again at peace,” said temple manager Vo Quang Minh, referring to Tac’s deathbed request to then-Prince Norodom Sihanouk. In November 2006, his remains were finally sent to be interred at Tay Ninh, bringing to an end nearly a half century of exile in Phnom Penh.

But whether Vietnam remains a truly “peaceful” place for Caodaists remains unclear. Although the Caodai militias initially fought alongside the communist Viet Minh against the French authorities during the 1940s and 1950s, they turned against them once the colonists were expelled in 1954. Following the fall of Saigon in 1975, the communists took their revenge, confiscating Caodai property and arresting or exiling many of its leaders.

Vo Quang Minh said that relations between the Cambodian Caodai and the Vietnamese government were difficult during the occupation of the 1980s, but have since improved. But despite some positive changes, rights groups and exiles say the Vietnamese government continues to ban participation in independent Caodai factions and oversees all internal Caodai affairs.

“Undercover government agents have infiltrated the administration of Caodai, and the religion has to function according to the government’s [rules] without respecting the current religious constitution,” said Hum Dac Bui. “The Tay Ninh Holy See has become more or less a place of tourist interest for the profit of the government, and is totally paralysed from a religious point of view.”

Brad Adams, Asia director of Human Rights Watch, said that only the government-approved Caodai sect is legally recognised, and that those who belong to splinter groups are subject to “harassment, arbitrary detention, and imprisonment”. In September 2004, he said, 12 Caodaists from Vietnam were arrested in Phnom Penh when they attempted to deliver a petition to delegates attending an ASEAN meeting. After being deported to Vietnam, nine members of the group were sentenced to prison terms of up to 13 years on charges of undermining Vietnam’s national security.

Adams added: “Cambodia is generally much more free with regard to freedom of religion than Vietnam, whose government sees unregistered church groups… as a threat to the authority of the Communist Party.”

But Tong Dinh Duong, 30, a member of the Saigon Caodai temple on Tran Hung Dao Boulevard in Ho Chi Minh City, told the Post last year that whatever the political situation, Caodaism’s unique blend of Western mysticism and Eastern philosophy would prevail. “When religion combines these together, people living together in the future won’t fight together,” he said. “In the future, we will have peace.” WITH REPORTING BY SAM RITH

[Published in the Phnom Penh Post, July 13, 2009]

2 comments

Chào ngày mới 09 tháng 11 | Chào ngày mới says:

Nov 8, 2014

[…] ^ http://www.sebastianstrangio.com/2009/07/13/under-the-gaze-of-the-divine-eye/ […]

Chào ngày mới 07 tháng 1 | Tình yêu cuộc sống says:

Nov 21, 2015

[…] ^ http://www.sebastianstrangio.com/2009/07/13/under-the-gaze-of-the-divine-eye/ […]